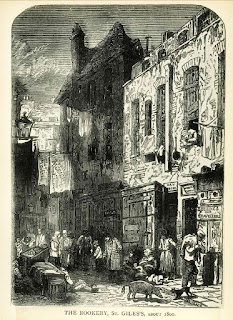

A True Fiery Hell on Earth: The London Tooley Street Fire of 1861 and the Victorian Spectacle of a City in Flames

On June 22, 1861 the day of the fire, Arthur Munby, a local resident who was attempting to get back to his home via horse drawn omnibus in London that night, wrote in his diary, “From Epsom and Cheam we saw a great fire in the direction of London. A pyramid of red flame on the horizon sending up a column of smoke that rose high in the air and then spread like that over Vesuvius.”

What Munby was describing as he rode towards his home that summer night was the infamous 1861 Tooley Street Fire--the largest conflagration to consume London in nearly 200 years since the Great Fire of 1666.

The Tooley Street Fire of 1861, parts of which would burn continuously for up to two weeks, was started sometime around what we today would call rush hour at about 5 in the afternoon on Tuesday, June 22. It is believed that at about that time, as a warehouse worker was closing up shop for the day along one of London’s many wharves packed with textiles, specifically at a place colloquially known as “Cotton Wharf” where tens of thousands of bales of cotton sent straight from the Confederate States of America to London were stored, that the stump of a still burning cigar was tossed carelessly aside, or that the still smoldering embers of a pipe were nonchalantly emptied into a cotton bale and caused the largest and most destructive fire in London’s thousand year long history of large and destructive fires.

Some have speculated that a form of spontaneous combustion among the densely packed textile warehouses of Cotton Wharf started the fire, but regardless, once the fire got going a deadly combination of dry summer heat, gusty winds and tons of jute, hemp, cotton and dry fibers created the perfect storm ideally designed to cause a spark to become a raging inferno of death--a true fiery hell on earth.

|

| View of the Fire after Two Days |

Our eyewitness, Arthur Munby, making his way slowly home that night, described the scene thus, “Through the trampling multitudes, shouts and cries of roaring flames and ominous thunder, the air full of sparks and the night a blaze of light, our omnibus moved slowly on…”

His omnibus moved slowly on into a real-life 1861 version of Dante’s Inferno set by history and by careless chance right in the heart of Victorian London, the western world’s largest and most densely populated city at the time. As already mentioned, what became known variously in the newspapers as either “The Tooley Street Fire” or “The Cotton Wharf Fire” wasn’t the first, or tragically the last fire in London’s history but it was the most destructive and the largest in memory. As Arthur Munby wrote in his diary, presumably after he arrived safely home that night, “No such fire has been known in London since the Fire of 1666…two millions, at least of property destroyed, acres of ruin, many lives lost…the fire was at its height two or three hours after I saw it, but it is still (Wednesday afternoon) burning furiously…”

And continue to burn it did, unlike any other fire anyone in the nineteenth century world had ever seen before.

Only minutes after 5 pm that dreadful afternoon the London Fire Engine Establishment was alerted. At the time, the London Fire Engine Establishment which in a few years time would be rechristened the London Fire Brigade was one of the world’s most advanced and largest fire fighting forces, but it wasn’t anywhere near large or advanced enough to stifle the Tooley Street Fire.

For one thing, the London “Fire Engines” that were brought to bear on the growing flames had nothing to do with self-propelled and powered engines in the modern sense of the word. London’s Victorian-Era fire engines, despite being cutting edge technology for the time, were hand drawn “button pushers”.

In order to operate button pusher Victorian fire engines teams of dozens of immensely strong and almost recklessly fearless men were needed to drag the enormous lumbering wheeled pumps as close to the raging flames as possible without being incinerated, and once that task was accomplished, dozens of other strong men were needed to operate enormous wooden levers designed to help pump water through unwieldy rubber hoses in the fire’s general direction.

|

| Artist's rendering of the fire |

Fire fighting in the Victorian Era was, by its very nature, exhausting work that was more suited to beasts than men, and more often than not as was the case with the 1861 Tooley Street Fire, it was a purely losing battle. But to their credit and thanks to their inestimable bravery, within less than an hour by 6 pm that evening 14 button pusher fire engines--the entire force of the London Fire Engine Establishment and even some fire engines that were privately owned--were on the scene of the Tooley Street Fire and heroically battling the blaze. During the Victorian Era, with multiple open flames being both in and around everyone’s home, and with candles and gas lamps lighting the inside of even densely packed apartment buildings, it was very common for businesses and even wealthy private individuals to own their very own personal fire engines and water pumps.

It hadn’t rained in weeks; the air was dry and despite the best efforts of the Fire Engine Establishment and heroic citizens the fire continued to rage and spread. Fire fighters attempted to pump water straight from the river Thames and into their engines to extinguish the blaze but due the recent drought conditions the water levels on the river were too low.

Soon, the Fire Establishment was forced to retreat with their backs against the river and watch the warehouses burn. After 6 o’clock dozens of buildings containing tons of spices went up in flames and a thick miasmic and choking cloud of burning pepper was added to the choking smoke of the burning buildings.

|

| Early Victorian Era Fire Engine From Edinburgh, Scottland |

Reynold’s Newspaper, a leading London weekly tabloid of the time reported in its June 30, 1861 edition, “Under the fallen floors of the warehouses and in cellars underground was a vast quantity of combustible material. Casks of saltpetre and casks of oil and turpentine, with hundreds of tons of sugar, cheese and bacon…”

|

| Fire Establishment using Hand Pumped Fire Engines |

A little over two hours into the blaze the Fire Chief, who had honorably served as a brave firefighter for more than thirty-five years and is even today still responsible for the evolution of many modern firefighting techniques--Superintendent James Braidwood--died when a section of a burning warehouse collapsed on top of him. He had been going from fire engine to fire engine running through flames to keep his men’s spirits up by handing out brandy rations when he was killed. As the sun set, the firefighters couldn’t hope to extinguish the flames, but they did contain them to one largely industrial area--free for the most part of civilians--called “Cotton Wharf” that was the import and export center of London.

As the fire was contained to one area of the city at around 10 o’clock that night something unexpected, most unusual and maybe even a little macabre occurred. Over 30,000 people in London came outside that night to watch the orange flames dance, the pall of gray smoke rise up into the sky with the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral framed majestically in the background and watched the city’s wharves and warehouses burn.

Reynold’s Newspaper reported, “And still the people came in fresh thousands to view the sight. Dawn of Sunday (over 5 days after the fire started!) found London Bridge still thronged with cabs, omnibuses, carts and vehicles of every description.” Enterprising food cart vendors took to selling sweetmeats and even beer as refreshment as thousands of onlookers gathered throughout the following two weeks to gawk at the spectacle of London’s Cotton Wharf on fire.

At any one time throughout the two weeks that the fire continued to burn upwards of 30 police officers had to be on patrol throughout the day and night just to guard against looters, rioters and wayward spectators walking into the path of the flames that were still being battled by the London Fire Engine Establishment.

When all was said and done, dozens of brave members including their esteemed leader, of the heroic London Fire Engine Establishment were killed in the Tooley Street fire mostly by flaming buildings which fell atop their heads. Burning tallow wax and other debris flowed from the wharf and into the River Thames making London’s main maritime artery impassable to ship traffic for weeks. Over one quarter mile of the city burned to the ground during the two weeks of the Tooley Street Fire of 1861. The fire caused the equivalent of over $300 million in damages in today’s money and since the fire itself started in and ended up consuming one of London’s most economically necessary areas, and because it devastated shipping for months, the real cost is truly incalculable.

However, some good did come of the fiery hell that was the Tooley Street Fire. The House of Commons launched an investigation in 1862 and reformed the insurance system for business owners. Additionally, in the aftermath of the fire Parliament enacted new laws that required safer storage of combustible and flammable material, and also in the aftermath of the fire starting in 1862 it became illegal to build warehouses that were attached to one another--space now had to be left for safety between buildings used for storing different goods and materials. And probably, most notably of all, due to the Tooley Street Fire of 1861 the London Fire Engine Establishment was greatly expanded, new firefighting technologies and safety equipment--including the use of iron “fire safe” doors and reinforced roofs in industrial buildings--was mandated. The bravery of the Fire Engine Establishment was celebrated in the press; firefighters were lauded as fearless public servants and the world famous London Fire Brigade was born.

Today, a plaque and statue immortalizing the London Fire Engine Establishment’s brave Superintendent James Braidwood stands at the corner of Battle Bridge Lane and Tooley Street where he gave his life so long ago to put out the fire that gave birth to London’s modern fire department.

Good article. One reason it’s public profile is not as well known as other London fires is that Tooley Street is on the South bank of the river Thames and thus was no threat to the financial City of London that is located across Southwark Bridge. Sadly another 80 years would pass before both areas would be raised to the ground by the German Blitz in 1940- May 1941

ReplyDeleteGreat point! Thank you for taking the time to read and comment on Creative History. I really appreciate it.

ReplyDeleteFascinating. Will share with my sister. Surprised I hadn't heard about it before.

ReplyDelete