Give Us Back Our Eleven Days! When Eleven Days in September of 1752 Simply Disappeared and the Historical Urban Legend it Created

Imagine a world where the day to day calendar--something as simple as what day in the year it actually is--could vary from place to place. The New Year might begin as late as March 25th, or much earlier, and things like holidays and the start and end of the seasons could fluctuate from year to year based on the phases of the moon or some other quirk of astronomy much like Easter Sunday and Passover week do to this day.

Well, that is exactly the type of world that citizens of Great Britain and her colonies--including our forefathers here in America--lived in until the year 1752. In that momentous year everything changed. Our calendar was completely reset, eleven days from the month of September simply vanished into thin air and for a brief moment in time the entire English speaking world nearly descended into chaos--or did it?

But not everyone lived that way until as recently as 1752. In fact, most Catholics (and many other people who weren’t quite as fiercely Protestant as our Puritan ancestors) already lived under the exact same calendar that we live by today and had done so since the year 1582!

In the year 1582 Pope Gregory XIII set about changing the ancient Roman Julian Calendar to simplify the observance of Catholic Saints’ Feast Days and also to make it easier to forecast the exact dates of Ash Wednesday, Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Pope Gregory also hoped that a simplified and universal calendar would help facilitate travel across the world which would then enable explorers primarily Spanish, but also others on behalf of Holy Roman Empire to more easily exploit the riches of the New World and increase the coffers of the Vatican. Therefore, in the year 1582 the “Gregorian Calendar” was born. The Gregorian Calendar set January 1 as the first day of the year, it made provisions for leap days every four years, standardized seasons, the 365 day year and the observance of holidays. It is, with a few minor changes, the primary calendar that the entire world uses today well over 400 years later.

|

| Pope Gregory XIII |

It is one of history’s most peculiar ironies that the Roman Catholic Church of the 16th century--the same institution that was then vilifying and excommunicating astronomers and others who dared to claim that the earth revolved around the sun and (along with Puritans!) burning witches at the stake--single handedly with the use of a Papal Bull enacted one of the world’s most important scientific achievements when it standardized the passage of time and created the calendar that we all use today.

However, as great as the Gregorian Calendar was (and still is) recently converted Protestants, like those in Great Britain weren’t buying it. In fact, they didn’t buy into it for 170 years! And when they did nothing as lofty as a divinely inspired Papal decree caused them to adopt our modern calendar, but rather, the whole thing came about through something as mundane as a simple act of Parliament.

That Act of Parliament had several names depending on who or where you were. The British Parliament completely discarded the word “Gregorian” and avoided any reference to Popes or the Catholic Church like it was the plague. The official name of the Act in His Majesty King George’s government was simply the Calendar New Style Act of 1750. The American colonists across the Atlantic somewhat derisively called it the British Calendar Act of 1751 and eventually the general public everywhere, and the British Press not without a touch of animosity would simply call it “Chesterfield’s Act” after the Member of Parliament who had become the Act’s biggest proponent in the House of Lords.

Lord Chesterfield, who was originally born Philip Stanhope and whose official title was the 4th Earl of Chesterfield,, in the year 1751 was fifty-seven years old and had been in Parliament, first the House of Commons and later the House of Lords after the passing of his father, since 1715.

Though remembered by most today for the British ale that bears his name, in his own day, Lord Chesterfield was a sort of political and literary celebrity. In the 18th century many considered him to be among the greatest living writers to have ever lived. He fancied himself an intellectual though his critics called him a foppish sort of dandy, and his reputation for elitism caused his memory to fall out of favor after his death.

In fact, Chesterfield was so famous in his time that the memory of him appears in one of Charles Dickens earliest novels, Barnaby Rudge. In that novel one of Dickens' more absurd characters says of Chesterfield’s literary pretensions, “Shakespeare was undoubtedly fine in his way; Milton good, though prosy…but the writer who should be his country’s pride is my Lord Chesterfield.

|

| Lord Chesterfield |

Needless to say, Chesterfield and many of his supporters in the House of Lords had a rather high opinion of themselves, and this group in 1750 formed a sort of intellectual Parliamentary caucus that successfully won debates in the House of Lords and caused Great Britain to implement the Gregorian Calendar.

In that momentous year of 1752, after nearly two years of political wrangling, the date January 1 began the official start of the new year for Great Britain and all of her colonies. In order for dating to catch up to the rest of the world and to successfully integrate the Gregorian Calendar into the “Old Style” dating that had been used in Britain and her colonies (where typically March 25th marked the start of a new year) and there weren’t even twelve months in a typical old style calendar year to begin with--it was decreed by Parliament that September 2, 1752 would immediately be followed by September 14, 1752. The logic behind this is sound but the explanation behind it all can be very long-winded and rather obtuse. The most important thing, historically to remember, is that over 11 days simply disappeared from the year 1752 in the United Kingdom and her colonies, and as could be imagined, not everything went smoothly.

No less a personage than perhaps Great Britain’s most famed artist and social critic of the last four hundred years William Hogarth who was known for his support of the English poor said of the Act’s passage, “The objection to this regulation, as favoring a custom established amongst papists, was not heard indeed with the same regard as formerly.”

Hogarth felt, as did many in Britain, that a group of pompous intellectuals, who were disconnected from the great majority of the people, had forced the New Style Calendar Act through Parliament, driven by their own upper class European (read here Catholic) agenda. Hogarth went on to say, “Yet many the president of a corporation club harangued upon as an introduction to the doctrine of transubstantiation, making no doubt that fires would be kindled again in Smithfield before the conclusion of the year.”

|

| William Hogarth and his beloved dog |

What Hogarth is reporting here is that many businessmen were stirring up the populace by denouncing the so-called Lord Chesterfield Act as Parliament’s first step in forced conversion to Catholicism. His reference to fires being kindled again in Smithfield hearkened back to devastating riots and peasant revolts that had occurred in London during the fourteenth century. Hogarth was saying that since Parliament insisted upon adopting the New Style Calendar Act then there would literally be violence in the streets.

Well, there wasn’t quite blood in the streets, but as could be imagined there was a lot of confusion. And there were protests. In the midst of a Parliamentary Election of 1754 crowds did take to the streets to assert their Britishness (keep in mind that all of this is occurring just as the nation is being swept by a tide of Patriotism at the start of the Seven Years War) by chanting, “Give Us Back Our Eleven Days!”

The Tories, then the more conservative party in Britain, using the passage of the Calendar Act in 1752 as justification levelled anti semitic and anti-Catholic accusations at their political opponents. The Tories accused government officials and members of the other political party (Whigs) of hatching devious “Jewish” backed plots and of being in collusion with the Pope and following orders from the Vatican.

|

| London Newspaper Detailing the New Calendar 1752 |

Though most historians today agree that there was really no rioting among the general public, there definitely was a lot of confusion about dates that took several years to rectify because eleven days did simply disappear.

The British Parliamentary Elections of 1754, against a backdrop of anti-semitism, anti-Catholic sentiment and fervent Patriotism, were some of the most vitriolic and violent in British representative history up to that point but most historians today agree that the New Style Calendar Act was simply used as an excuse to justify abhorrent political behavior that most likely would have occurred anyway.

It is truly difficult to accurately ascertain what the average man or woman in Great Britain, or her colonies for that matter, actually thought about the calendar change and how they specifically felt about randomly losing twelve days of their life in September of 1752.

Undoubtedly, many people did hold the mistaken belief that the passage of the New Style Calendar Act and its implementation in 1752 robbed them of eleven days and thereby made their lives eleven days shorter then they would otherwise have been. This is the impetus behind the chant of “Give Us Back Our Eleven Days!” a sentiment that tories exploited to the fullest during elections in the 1750’s.

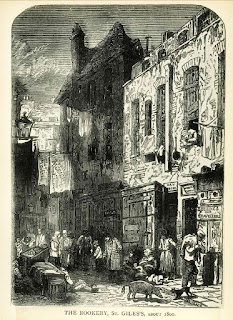

The painting, by William Hogarth of course, used at the start of this article shows a chaotic government meeting where protesters carrying signs reading, “Give Us Back Our Eleven Days!” can be seen walking in the streets outside through the window.

And I’m sure some people felt that their Holy Days like Good Friday and Easter Sunday were being hijacked by a “Catholic” calendar, but many local writers of the time also noted how the night of September 2, 1752 was one of partying and festivity with ordinary citizens being enamored by the fact that the next day would simply just become September 14, 1752 as if by magic. In reality, it seems like most ordinary people celebrated that calendar change as if it were the second New Year’s Eve celebration of the year!

Today, most historians are in agreement that no riots, and little violence ever took place, as a direct result of the New Style Calendar Act being implemented in Great Britain and her colonies. Most people agree that the concept of mass rioting and chaos as a result of 11 missing days in September is an historical form of “Urban Legend” that sounds plausible, but in fact, never happened at all.

Still, it is odd to think that September 2, 1752 was followed by September 14,1752 and it would definitely be a natural human reaction to protest, insist even, and chant--Give Us Back Our Eleven Days!

For More Information Check out this Informative Article from HIstoricUK: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Give-us-our-eleven-days/

Comments

Post a Comment