I Have Killed a Principle: The Story of Gaetano Bresci the Anarchist from New Jersey who Shot the King of Italy in 1900

It is mid-afternoon on July 29, 1900.

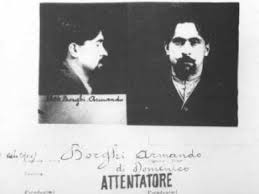

Gaetano Bresci is a thirty year old Italian-American immigrant; he’s married to an Irish-American woman named Sophie Kneiland who grew up in Hoboken, with whom he has fathered two young daughters. Despite being a devout family man, which by all accounts Gaetano Bresci most definitely was, he is also an anarchist.

He had immigrated to New Jersey several years before after running afoul of Italian legal authorities for publishing supposedly dangerous and insurrectionist anarchist literature. Bresci eventually settled in Paterson, New Jersey, a hotbed of anarchist meetings and activity in the United States, where he was able to not only continue to carry on his war against all world governments, but also able to support his growing family by finding work as a silk weaver.

Gaetano Bresci is an anarchist who has sworn revenge against King Umberto I of Italy--the King that Bresci refers to as, “The Murderer King.” For the purpose of revenge on July 29, 1900 Bresci arrived in the Italian town of Monza with a .38 caliber pistol in his pocket.

Bresci and his wife Sophie have spent weeks practicing shooting the .38 caliber pistol while they picniced with their children in the many woodland parks that surround Paterson in the year 1900.

King Umberto I is by all accounts a lackluster, and if anything, a negligent but not a murderous monarch to be sure. In fact, at the very moment that Gaetano Bresci arrived in Monza on July 29, 1900 at the royal summer residence, King Umberto was busy handing out awards to distinguished Italian athletes who had most recently competed at the Paris Olympics of 1900.

|

| King Umberto I |

It is said that King Umberto was, “Passionately fond of horses and hunting,” and that he was, “Remarkably regular in all of his habits.” The King woke up at six in the morning everyday and visited his many stables first thing upon waking up. Every day around noon he visited his mistress, a woman he had kept up a clandestine love affair with despite his being married for over thirty years. And every afternoon he drove in the same carriage, at the same hour on the same route through the royal gardens outside his summer palace.

All of these very regular, and fastidiously punctual habits of King Umberto I played right into the hands of Gaetano Bresci and his plot for revenge against “The Murderer King.”

On the afternoon of July 29, 1900 on his ride through the royal gardens a man stepped in front of the royal carriage and stood less than six feet away from King Umberto I.

That man pulled a .38 caliber pistol from his pocket and shot the king twice in the chest.

For a moment the king, “Gazed at the man reproachfully,” and then he fell over against the shoulder of his closest aide before murmuring, “Avanti!” and then dying there on the spot. (Tuchman 104)

The assassin stood transfixed and holding his smoking gun high in the air with what witnesses said was a look of triumph on his face before being immediately seized and wrestled to the ground he shouted, “I did not kill Umberto. I have killed the King! I have killed a principle!”

Gaetano Bresci had gotten his revenge.

In many ways Bresci’s life, though it had taken him from Italy, to New Jersey and then all the way back to Italy again in only thirty short years, had been on a collision course with this very moment from the second that he was born.

|

| Bresci Assassinates Umberto I July 29, 1900 |

He had started work at the age of ten as a silk weaver in Prato, Italy. Weaving silk was the family trade, a trade he would one day take with him to America by way of Paterson, New Jersey, but when Gaetano Bresci was born near the end of 1869, his lower income family lived on an Italian peninsula rife with warfare and starvation. Everyone, even the children, had to work just to survive and Gaetano Bresci, despite being highly intelligent, a devourer of any books he could lay his hands on, and an auto-didact who taught himself several languages, never had the luxury of a formal education.

By the age of fifteen Bresci had already become a radicalized anarchist while still working in Prato’s carpet making sweat-shops. He had become opposed to any and all state control and any and all forms of centralized government. Young Bresci wasn’t alone.

During the last decades of the 19th century, to many more conservative people across Europe and the United States, it seemed as if bomb throwing, gun-wielding anarchists were everywhere--ready to wreak havoc and rip the old world order asunder at the merest drop of a hat or the least provocation.

Though in reality violent action by most anarchists was pretty rare, and almost never successful between the years 1880 and 1920, to the more staid elements of European and American society that fact didn’t much matter. As far as the average man or woman on the street in western Europe or the United States was concerned, any and everyone could be blown to pieces or shot in the head at any moment by a radicalized, left-wing (most likely Jewish, Irish or Italian) self-proclaimed anarchist.

In the year 1900 when Gaetano Bresci assassinated King Umberto in one of the few successful acts of “Propaganda of the Deed” as the Anarchists themselves labeled it, Anarchism was viewed by most as the Islamic Terrorism or Red Scare of its time.

However, though anarchism as a movement did gain many adherents among the multitudes of oppressed and poor working men and women in the western world, it had one glaring problem that forever kept it from going mainstream, so to speak, as a political movement in the same way that Socialism, Communism or even Fascism did at the time.

By their very nature, and by their very own philosophy, anarchists abhorred all efforts to organize and form a codified structure. Any attempt at centralized leadership for any type of international Anarchist Party was nearly impossible, though many efforts were made in the years leading up to the twentieth century to centralize the worldwide anarchist movement.

Realizing that their own movement was incapable of generating any organized resistance, eventually as the twentieth century dawned, many anarchists began to preach the doctrine of “Propaganda of the Deed”. The idea behind Propaganda of the Deed was that one anarchist would commit one brazen and violent act, such as an assassination or a bombing, that would then propel the working masses across the world to rise up against all forms of centralized government, but particularly against forms of absolute monarchy.

Gaetano Bresci and his dream of revenge against King Umberto I of Italy, the so-called Murderer King, made him the ideal candidate to commit ‘Propaganda of the Deed’ and spur the oppressed working masses to rise up.

There was one particular event that most spurred Bresci onward in his quest for revenge--The Bava Beccaris Massacre.

The Bava Beccaris Massacre, which was named after the Italian General who ordered it, occurred in May of 1898 when over eighty demonstrators were shot in cold blood by Italian troops as they protested against the high price of food in Milan.

Back in Paterson, New Jersey, the Bava Beccaris Massacre in Milan outraged Gaetano Bresci and caused him to vow revenge against King Umberto, but among New Jerseyians at the time, Bresci was definitely only one outraged anarchist among many.

|

| Paterson New Jersey in 1900 |

Around the year 1900 northern New Jersey was filled with working class men and women who labored in manual trades for veritable slave wages in populous urban centers like Paterson, Newark, Jersey City and especially New York. These men and women lived hard-scrabble hand to mouth lives, constantly teetering on the edge of starvation, and many banded together in trade unions from which more radical anarchist movements, like the ones that Gaetano Bresci was part of, recruited their members.

In Paterson, Bresci was a founding member of a group called “The Right to Existence” an anarchist group made up primarily of New Jersey’s Italian-American working poor. He helped publish, in both English and Italian, a weekly anarchist newspaper called The Social Question (La Questione Sociale in Italian).

But, after the Bava Beccaris Massacre, Bresci considered the Right to Existence group not radical enough and he left and set about on his quest for revenge against King Umberto I of Italy. Though, it should be noted, that it was funds raised by locally based anarchists in Paterson and surrounding parts of the Garden State which eventually enabled Bresci to legally purchase a .38 caliber pistol and also paid his passage back to Italy for his murderous rendezvous with King Umberto.

After his assassination of King Umberto I, while in prison, Gaetano Bresci, the lowly anarchist silk weaver from Paterson, New Jersey, became an international celebrity overnight. Anarchists from around the world sent, or tried to send Bresci letters of congratulations on his brave act of assassination while he was in prison.

He was lauded by many for achieving the goal of “Propaganda of the Deed”, but alas, there was no uprising among the poor; no trend toward anarchism or abolition of other monarchical governments around the world.

Bresci’s trial began on August 30, 1900. Luckily, for him anyway, the death penalty had been abolished in Italy under the rule of King Umberto I as an act of humane progressivism.

Both the Italian and American governments were convinced that Gaetano Bresci’s assassination of King Umberto had been part of some larger anarchist conspiracy and many were arrested, including eleven people in New Jersey, and held in solitary confinement for the duration of Bresci’s trial without any charges against them.

In the end, no proof of any anarchist conspiracy in either New Jersey or Italy was ever revealed and all of those unlawfully detained in connection with Gaetano Bresci were eventually released.

Bresci was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment--the harshest penalty that could be given to any convict under Italian law at that time.

On May 22, 1901 less than a full year after his conviction Gaetano Bresic was found hanging by the neck in his prison cell with the word “Vengeance” carved into the wall near his lifeless corpse. His cell was supposed to be under constant twenty-four hour surveillance by prison authorities and his death was ruled an apparent suicide. To this day many question whether or not foul play was involved in the death of Gaetano Bresci.

|

| Bresci's apparent suicide |

And to this day Gaetano Bresci is revered by Anarchist movements around the world as a cult hero representative of a successful act of “Propaganda of the Deed”.

Works Cited

Tuchman, Barbara W. The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the

War 1890-1914 Pub. Ballantine Books 1966

All photos courtesy of Wikipedia

Comments

Post a Comment