Modern History's First Humanitarian: The Horrors of the Battle of Solferino and the Triumph and Tragedy of Jean Henry Dunant

“No quarter is given; it is sheer butchery; a struggle between savage beasts maddened with blood and fury. Even the wounded fight to the last gasp. When they have no weapon left, they seize their enemies by the throat and tear them with their teeth…”

The text quoted above is from a work of narrative military history published in 1862 entitled A Memory of Solferino. It was written by a Swiss banker, a gentleman and a devout Christian, who happened to be an unexpected witness to one the 19th century’s largest and most ferocious battles on mainland Europe.

That man was Jean Henry Dunant who today is best remembered for winning the inaugural Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 and for being the founding inspiration behind the formation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Today, the Red Cross in conjunction with its partner organization, the Red Crescent, is the single largest and most influential humanitarian organization in the world and it all began on a bloody battlefield in northern Italy outside the town of Solferino in 1859.

|

| Dunant's Draft of A Memory of Solferino |

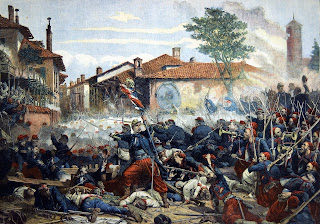

Fought on June 24, 1859 the Battle of Solferino was a decisive engagement in what historians today call the Second Italian War of Independence. It was the largest battle fought on the European continent until 1916 and the Battle of Verdun during the First World War. The engagement at Solferino involved over 300,000 men from a combined French and Italian army opposing the forces of the Austrian Empire.

It was a decisive victory for the combined Franco-Italian army but the human cost on both sides was extremely high, nearly unconscionable in fact, for the time.

In total over 11,000 men were killed in action, more than 25,000 were wounded and approximately 5,000 were listed as missing (most likely killed but with their bodies mutilated beyond all recognition) in one single day of combat.

This amount of death and destruction was staggering for warfare up to that time and in many ways was a bloody prelude to the combat of the American Civil War of the 1860’s and of World War One in Europe from 1914-1918. And though, militarily and politically, the Battle of Solferino was decisive in gaining independence for many Italian city-states from the Austrian Empire, and though it helped to increase French influence and hegemony on continental Europe under the rule of the Emperor Napoleon III, perhaps it could be said that the Battle of Solferino fought between France, Italy and Austria did more for the cause of world peace than any other single military engagement before or since.

And it was thanks to one man, Jean Henry Dunant, that the horrors of one of the nineteenth century’s bloodiest battles became a rallying cry for peace and humanitarianism around the world.

Dunant wrote a book, an anti-war magnum opus dedicated to peace, about the savagery, brutality and suffering that he witnessed firsthand in the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino in June of 1859 called simply A Memory of Solferino.

In A Memory of Solferino Jean Henry Dunant spoke not only of the horrors of war that he witnessed but he also, as a Christian and a humanitarian, posed the question of why humanity couldn’t do better when it came to easing the suffering inflicted as a result of the man made calamity that was modern warfare.

Dunant asked rhetorically in his writing on modern 19th century warfare, “Would it not be possible, in time of peace and quiet, to have relief societies formed for the purpose of having care given to the wounded in wartime, by zealous, devoted and thoroughly qualified volunteers?”

Duant, after witnessing the human tragedy that resulted from the climactic Battle of Solferino was one of the first to speak of the plight of civilians caught up in what he called the ever more destructive advancement of modern war. He applauded local women who tended to the wounded and to the neglected prisoners of war, and he made no distinction between combatants and non-combatants from both sides.

|

| Jean Henry Dunant in the 1860's |

When it was published in 1862 A Memory of Solferino became an immediate international bestseller and a rallying cry for humanists and pacifists worldwide who feared the ever growing destructive power of modern nineteenth century warfare and realized that the world’s major powers were caught in an arms race which, in the end, led within the first two decades of the twentieth century to the human cataclysm that was World War One.

A Memory of Solferino was not only unique at the time of its publication for being a work of anti-war humanism, but it was also an astute and well-written work of narrative social history that highlighted, in human terms, the plight of average men and women caught up in a war of empires and monarchs at a time when even the mere existence of the average man and woman was largely ignored by historians who typically only wrote dry works that dealt with the strategy behind military engagements and political machinations.

Not only did A Memory of Solferino prove that Jean Henry Dunant was a wonderful writer and an accomplished historian, but today it is also considered to be the one single work that directly led to the foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the adoption of the Geneva Convention for more humane rules to govern the conduct of warfare worldwide.

Oddly enough though, Jean Henry Dunant, banker, businessman and devout Calvinist Christian from Geneva, Switzerland, never planned on being an eyewitness to one of the largest land battles in European history in the first place. By Dunant’s own admission he wrote, “I was a mere tourist with no part whatever in this great conflict, but it was my rare privilege through an unusual train of circumstances to witness the moving scenes that I have resolved to describe.”

A mere tourist? Maybe, not exactly, but Jean Henry Dunant was by no means a combatant. He had a banking interest in Algeria, one aligned with Napoleon III of France, and coming from a long line of Swiss bankers the well traveled Dunant had gone to Italy to speak with the Emperor Napoleon III about some bank matters related to the French colony of Algeria. Although Dunant was an acquaintance of Napoleon III, and hoped to catch up with the Emperor somewhere in Italy, it does not appear that he ever expected to witness the horrors of war that he saw and later put into writing in A Memory of Solferino.

This is not to say that Jean Henry Dunant was some sort of money chasing Swiss banker and businessman of the 1800's, in fact, he always was far from that even prior to witnessing the horrors of battle and dedicating himself full-time to alleviating the sufferings of humanity.

Though having been born into a wealthy family, and having had all the advantages that came with being a member of Europe’s banking aristocracy, Jean Henry Dunant was also raised in a devoutly Christian family and absorbed and put into practice the Christlike ethos that had been taught to him from an early age.

All who knew him, even as a boy, said that Jean Henry Dunant was always a man of high moral conscience, and as a young man, he seemed to bounce from noble cause to noble cause.

For a time, as a student, Dunant was an active member of a group called the Union of Christians and Jews, which sought to end anti-semitism in Europe during the 1830’s and 40’s. After he tired of that cause Dunant joined a group called The League of Alms, which sought to alleviate the suffering of Europe’s poor and destitute. He first published written works in relation to prison reform and he used his business connections to travel all across the continent and bring about improvements in the living conditions of the incarcerated.

He was active in a group called the Young Men's Christian Union in Switzerland which was one of many Christian oriented service organizations that sprang up all across Europe and North American during the 1850’s. And it was thanks in large part to Dunant’s organizing efforts that the first ever worldwide conference of Young Men’s Christian Associates (today’s YMCA) was held in Paris in 1853.

But it wasn’t until the publication of A Memory of Solferino in 1862 that the humanitarian mission of the ever moralistic Jean Henry Dunant burst onto the world scene.

In 1863 Dunant was the chairperson of a five member committee that put his plan into effect to create a neutral international humanitarian organization to alleviate the sufferings of all of those caught up in the horrors of modern warfare. With Jean Henry Dunant at its helm 1n 1863 (at the height of the carnage of the American Civil War) the International Committee of the Red Cross was born.

Today, over one hundred and sixty years later the International Committee of the Red Cross’ mission statement has not changed at all. It is still the same mission statement that Jean Henry Dunant drafted after witnessing the horrors of the Battle of Solferino: “To Prevent and Alleviate Suffering in the Face of Emergencies by Mobilizing the Power of Volunteers and Generosity of Donors.”

To this very day the International Committee of the Red Cross recognizes Jean Henri Dunant’s work A Memory of Solferino as its founding document.

But, though Dunant did get to realize his humanitarian dream of founding an international organization to alleviate the suffering of others, only a few short years later, his reputation took a turn for the worse and his life was turned upside down.

In 1867 Dunant’s banking interest in Algeria, the same one which had caused him to be present to witness the Battle of Solferino in 1859 in the first place, went bankrupt and he ended up defaulting and being unable to pay back almost all of his investors. Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy and his family lost most of the fortune that they had spent generations building in the Swiss International Banking Industry. Dunant was shunned by society as the highly religious citizens of Geneva believed that debt was sinful and looked on Dunant as being, at the very least irresponsible, if not downright morally bankrupt for defaulting on so many loans with so many investors.

Due to scandal and shame by 1870 Jean Henry Dunant, the once proud founding member of the International Committee of the Red Cross, was forced to retreat into obscurity. He moved to Paris where he lived in poverty and, despite working even then for some charitable organizations, lived a lonely life apart by and large from others.

In July of 1887, thanks to the financial support of family members who took a sympathetic view of Jean Henry’s failed banking ventures, he was finally at the age of fifty-five and in failing health able to move back to his native Switzerland, where he resided in a small mountain village called Heiden.

It was while he was living out his old age in a hospital in obscurity in the small Swiss village of Heiden that Jean Henry Dunant returned to public memory and finally began to receive the credit that he deserved for being the founding member and the driving force behind the foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the world’s largest humanitarian organization.

|

| Plaque Commemorating Journalist Georg Baumberger |

In 1895, when Dunant was already nearly seventy years old, a young German journalist named Georg Baumberger who was the editor of a small newspaper decided to write a story on the International Red Cross and he traveled to Heiden to take a stroll with Dunant and ask him about the early days of the organization. Baumberger wrote an article entitled “Henri Dunant: The Founder of the Red Cross” and once again, after the passage of thirty years time, the humanitarian efforts of Henry Dunant and the pioneering work of narrative history that had been A Memory of Solferino burst onto the world scene. With the publication of Baumberger’s article and the reemergence of A Memory of Solferino as an international bestseller, all of Jean Henry Dunant’s banking transgressions were, if not forgiven, at least forgotten by most and he was celebrated worldwide as the humanitarian for peace that he had always striven to be throughout his life.

In 1901, at the age of seventy-three Jean Henry Dunat was awarded the world’s first ever Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in establishing the International Committee of the Red Cross. Upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize the International Committee of the Red Cross wrote a letter of congratulations to its founding member and said:

“There is no man who more deserves this honor, for it was you forty years ago, who set on foot the international organization for the relief of the wounded on the battlefield. Without you the Red Cross, the supreme humanitarian achievement of the 19th century, would probably have never been undertaken.”

Today, the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent is the largest humanitarian organization in the world and has a presence in almost every country worldwide, where to this very day, it still strives to fulfill the original mission statement as laid out by its founder way by in 1862 in his seminal work A Memory of Solferino.

|

| Jean Henry Dunant 1901 |

Jean Henry Dunant passed away in 1910 at the age of eighty-two in the same convalescent hospital in the small village of Heiden, Switzerland, where he had spent the last twenty-three years of his life.

Comments

Post a Comment