Evil May Day 1517: The Antil-Immigrant London Riots that Shocked Tudor England and Still Echo Today

May Day, the 1st day of May, was typically a day of feasting, festivity and celebration in early modern England. Ordinarily, in London May Day was a day off from work for the laboring masses and a day to gather in the warm Spring sunshine for dancing and sport in the city’s narrow streets. But, in London on the 1st of May during the fateful year of 1517, a day of celebration and revelry took on a much more sinister tone and became forever known to history as “Evil May Day”.

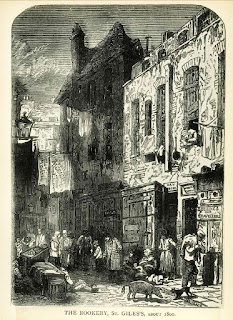

On the night of May 1, 1517 a violent and drunken mob which numbered perhaps in the thousands took control of old London’s densely packed, muddy and narrow late-medieval city streets. Fired by years of simmering rage over low wages and lack of meaningful employment, the angry mob sought to assault and in some instances even attempt to murder every member of London’s ever growing foreign born immigrant population that they could find.

At that time in Tudor England during the reign of King Henry VIII England’s immigrant population mostly from France, Holland, Germany and with a smattering of expatriate Italians and eastern European Jews, was known collectively by the native born English population as “Strangers” sometimes referred to as the Strangers by nativist firebrand preachers from the pulpit.

Most of the so-called “Strangers” who resided in London during the early part of the 16th century had immigrated from their homelands on mainland Europe to England (like most immigrants have done everywhere and for all time) in search of a better and more prosperous life for themselves and their families.

A few, however, had become inordinately wealthy and even gained influence with King Henry VIII at the royal court by exploiting England’s lucrative wool trade through dishonest business dealings with merchants abroad in continental Europe. Most immigrants lived in small ethnic enclaves, some by choice and some like the Jews by force, where they spoke only their native languages and were largely separated from London’s greater English population as a whole.

On the night of May 1, 1517 these ethnic enclaves French, Dutch, German, Italian and Jewish became flashpoints for rioting and murder and were burned to the ground. No group was spared from the wrath of the angry and vengeful nativist mob of Evil May Day.

London’s total population at the time was around 50,000 souls with approximately 1500 of those individuals being considered “Strangers” for having been born somewhere outside of England. And although for decades, perhaps even centuries, prior to May 1, 1517 there had been long-standing suspicion and prejudice towards London’s immigrant population, nothing as violent as the Evil May Day Riots of that day had ever occurred before in the city’s long history.

In late 1516 about six months prior to the Evil May Day riots, in a move that echoed Martin Luther’s ninety-five theses which would spark the Protestant Reformation within that same year, an unknown Londoner (but most likely someone involved in the printing trade) nailed a broadsheet piece of paper to the door of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The paper that was nailed to the cathedral door accused “Aliens” of “Dominating the wool trade.” It went on further to state that the “Strangers” in the city of London, “(A)voided paying customs duties on imports and exports,” and it accused all foreign born immigrant merchants of, “Having especial favor with the new King.”

And finally, most emphatically of all, the broadside that was nailed to the door of St. Paul’s Cathedral sometime around Christmas 1516 called for: THE IMMEDIATE EXPULSION OF ALL FOREIGN BORN STRANGERS FROM THE CITY OF LONDON.

Crowds gathered before St. Paul’s Cathedral to hear the anti-immigrant declaration read aloud and the broadside immediately sent shockwaves throughout the entire city. Apparently, nailing stuff to church doors was a very effective form of mass communication during the sixteenth century!

|

| Evil May Day Riots Begin May 1, 1517 |

Caught up with the anti-immigrant fervor was an equal disdain for King Henry VIII. It was known that the new King had an opulent appetite for the finest in Italian fashion and French cuisine. Despite himself being a Francophile, in 1517 upon ascending to the throne, King Henry VIII embroiled England in a costly war with France. Not only did London’s working class resent their new king’s close relationship with so-called “Strangers” but by early 1517 the populace at large had also been whipped up into a patriotic anti-French and thereby anti everything foreign fervor. It was a recipe for disaster.

And as the calendar turned from winter to spring things only got worse for London’s immigrant population. During Easter of 1517, less than a month before May Day, a respected theologian by the name of Dr. Bell made an outdoor speech in London that was attended by thousands in which he declared that, “Englishmen should cherish and defend themselves and hurt and grieve aliens.”

Leading up to Evil May Day 1517 blatant calls for violence against “strangers” “aliens” and the “foreign born population” were not only tolerated on the streets of London but rather commonplace.

During the last week of April 1517 attacks against immigrants, mostly in the form of beatings after dark, were commonplace on city streets. Royal authorities began to become concerned about the escalating anti-immigrant violence in the city but, unsure of what to do next and unwilling to further incite a restless populace to even greater acts of violence, no direct action was taken by the Tudor regime.

The Mayor of London under pressure from King Henry VIII did impose a 9 pm curfew for all of London’s residents in the days leading up to May Day 1517, but as there was no police force at that time and few soldiers within London’s city limits, the curfew was all but unenforceable and largely ignored by almost everyone.

On May 1, 1517 at around 10 pm a local alderman, an elected official who worked for the city council which would have been about the closest thing that London had at that time to a member of law enforcement, named John Mundy, observed a group of young men loitering on the street past curfew.

He approached the group of young men and questioned why they were still congregating on the street past curfew at such a late hour. Alderman Munday was accused of being a “Stranger” pelted in the head with a stone and forced to run for his life. Evil May Day 1517 had begun.

Slowly, what had begun as a group of drunken young men grew into a large and angry mob. Over a thousand people gathered in Cheapside, one of London’s poorer neighborhoods. The first thing that the ever growing mob did was to break into the city’s jails and let out all of those who had earlier been arrested for assaulting immigrants.

|

| 16th Century map of London |

Then the mob swept to the neighborhood St. Martin le grand, the French enclave in London, and began to drag French immigrants out of their homes in the middle of the night to beat them senseless and put their neighborhood to the torch.

Thomas More, sheriff of the city of London and famed writer and philosopher, attempted to reason with the mob and implored them to go home but his efforts, despite his fame and respectability proved futile. The mob only continued to grow and grow as the night wore on. Rioting became citywide with many London residents simply tossing large objects out their windows and onto the streets and there were many reports of boiling hot water being poured over the naked skin of immigrants that the nativist mob had captured.

A few soldiers, guards stationed at the Tower of London fired cannon and muskets at the crowd, but the soldiers were grievously outnumbered and soon overwhelmed by the bloodthirsty mob. Some rode out on horseback from the city to tell the King about the anarchy and violence that had descended that night on England’s largest city.

Only dawn, the sunrise and sheer exhaustion, could quell the rage and violence of the anti-immigrant mob on Evil May Day 1517. The next day a private army, knights on horseback recruited by and under the leadership of, the Duke of Norfolk rode into the city in a show regal force to stop the rioting and to keep the peace.

It is thought today that about 300 people were arrested once order was restored to the streets of London after Evil May Day 1517. The royal authorities sought to find the ringleaders, if any, of the anti-immigrant riot. On May 4, 1517 only three days after the riot, 278 individuals, some women and children among them, were charged with treason and brought before King Henry VIII.

|

| Crude Eyewitness Engraving of Evil May Day1517 |

Legend has it that Catherine of Aragon, one of King Henry’s many wives, pleaded with her husband to spare the lives of the rioters out of compassion for the women and children. As it was, only 12 men, those that the authorities considered to be the ringleaders of the Evil May Day Riots of 1517, were hanged, drawn and quartered. Although, the story about Catherine of Aragon begging the King for mercy makes for a nice anecdote, and though it may have a grain of truth to it, most likely King Henry VIII was more lenient towards the perpetrators of the Evil May Day Riots of 1517 than he normally otherwise would have been out of fear of a popular uprising over immigration and his dubious policies.

Violence against immigrant populations, though never again reaching the levels of Evil May Day 1517, would continue sporadically throughout London for years. Unfortunately, some would argue that violence like that demonstrated by London’s populace on the night of May 1, 1517 has continued, sporadically, across the western world against immigrant populations right down to the present day…

These stories are amazing! Please keep writing them!

ReplyDeleteThank You so much!

DeleteThe immigrants back then did far less raping of English children than the ones that are here today. Go ahead, look up the rape rings that are going on today.

ReplyDelete