Monsters, Men and the Victorian Media: The Story Behind the HMS Daedalus Sea Serpent Sighting of August 6, 1848

First launched in 1826 the HMS Daedalus was a forty-six gun top of the line frigate of the Royal Navy. Having never been used in combat in that capacity, after eighteen years of service in 1844, the HMS Daedalus was literally cut down in size and recommissioned as a smaller, faster more maneuverable nineteen gun Corvette of the Royal Navy.

On August 6, 1848 the HMS Daedalus was cruising in the south Atlantic about 300 miles off the coast of west Africa. The weather was dark and cloudy and seemed to presage the onset of a midsummer thunderstorm at sea.

At approximately 5 o’clock that afternoon midshipmen aboard the Daedalus alerted their officers to a most unusual sight. The ship’s Captain Peter M’Quhae along with the First Lieutenant and all of the ship’s officers rushed to the quarterdeck to view what the crewmen had described as a “sea serpent” swimming above the surface of the water alongside their ship.

|

| A Royal Navy Corvette of the 1840's similar to Daedalus |

Captain M’Quhae, an experienced mariner to say the least, with nearly two decades of service in the Royal Navy under his belt, stated in his official report:

“Our attention being called to the object it was discovered to be an enormous serpent with head and shoulders kept about four feet constantly about the surface of the sea.”

Another ship’s officer who viewed the supposed sea serpent that afternoon, but chose to remain anonymous in a report he gave to the London Illustrated News, sometime in October 1848 just after the Daedalus returned to port stated that, “The animal was moving at probably not more than ten miles per hour…the water swaying under its chest…it was not more than two-hundred yards away from the ship…the eye, the nostril, the color and form were all distinctly visible.”

To this day the sighting of a giant unknown serpent like creature in the waters of the south Atlantic by the crew of the HMS Daedalus remains one of the most well documented and controversial sea monster sightings in history.

From the very moment that the Daedalus returned from its voyage to its home port in Plymouth, England controversy and debate have swirled around what was, or was not witnessed, by the crew on that stormy day at sea in August of 1848.

|

| The Sighting took place about 300 miles off the coast of Namibia |

With the testimony of literally hundreds of sailors, and dozens of Royal Navy officers to draw upon, the story of the so-called Daedalus sea serpent immediately became a mid-nineteenth century Victorian Era media sensation.

The first report of the Daedalus’ sea serpent sighting, the after-action report of none other than Captain Peter M’Quhae was published in the London Times on October 10, 1848, less than a full week after the HMS Daedalus had returned to port.

Writing with both the detailed detachment that was demanded of a nineteenth century Royal Navy officer, but also with some of the emotion and wonder of a person who had just had a close encounter with the unexplained, Captain M’Quhae echoing the anonymous statement of his fellow officer in the London Illustrated News remarked that, “It passed rapidly, but so close under our lee quarter, that should it have been a man of my acquaintance, I should have easily recognized his features with the naked eye.”

What makes the Daedalus sea serpent sighting so remarkable is that so many officers and men of the ship were willing to stake their careers, reputations and even questions of their own sanity by publicly stating to members of the burgeoning Victorian print media descriptions of what they had seen; for that reason, even nearly two centuries later, the sighting by the crew of the HMS Daedalus still remains one of the best pieces of “evidence” that we have for the existence of sea serpents or unexplained cryptids of the sea.

The fact that the Daedalus sea serpent was sighted by crew members, including a substantial number of officers of the Royal Navy, gave reports of the sea monster instant credibility in British newspapers of the time.

Royal Navy officers were expected to be gentlemen, men who were cool under pressure and under fire, both literally and figuratively. By the middle of the 1800’s naval officers were, by and large, educated men with at the very least a working knowledge of mathematics, meteorology, navigation, marine biology and any number of other natural sciences. Men like Captain Peter M’Quhae were not normally given to telling yarns or tall-tales of the sea.

Newspaper readers across Great Britain greeted reports of what the press dubbed the “HMS Daedalus Sea Serpent” with wonder and astonishment, but that isn’t to say that the tale of the unknown sea monster wasn’t without its detractors.

Sir Richard Owen, was an English biologist and anatomist who lived from 1804 to 1892 and was known for his pioneering work studying ancient fossils. He is best remembered for coining the term “Dinosauria” (singular form: dinosaur) meaning “terrible” or “great reptile” in the 1840’s and for his criticism of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and the theory of evolution that it propounded in the 1860’s. Though Owen himself admitted that some form of evolution probably did occur within species, he believed that Charles Darwin’s take on the whole matter was far too simplistic and contained some glaring omissions.

|

| Sir Richard Owen |

Anyway, the purpose here is to not get bogged down in an age-old evolutionary debate, but rather to establish Robert Owen’s credentials as one of the most respected scientific minds in all of England during the mid-nineteenth century.

In the Autumn of 1848, in the wake of the HMS Daedalus sea serpent reports, Sir Richard Owen was on the faculty at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and literally rewriting our understanding of prehistory with his research into dinosaurs.

Only a week after it chose to break the story of the HMS Daedalus sea serpent by publishing a transcript of Captain M’Quhae’s official report, oddly enough, perhaps to simply stir up debate among the general public and sell more newspapers, the London Times published an interview with biologist Sir Richard Owen in which he stated that what the crew of HMS Daedalus most likely saw was, “(N)othing more than a large swimming elephant seal.” Owen went on to further suggest that what the crew of the Daedalus had interpreted as the serpent’s nearly sixty-foot long tail, was simply, “the wake left behind in the water by the swimming elephant seal.”

When Captain M’Quhae heard what the Times had published in direct contradiction to his official report, and when he read that famed biologist Sir Richard Owen had accused his crew of not being able to identify the body of a “giant swimming elephant seal” from that of an unknown sea serpent he was furious! And he fired back at his critics and detractors in the press immediately.

Unfortunately, for M’Quhae within weeks of his after-action Daedalus report all of this talk of sea serpents and sea monsters in the British press was causing the Royal Navy no end of embarrassment. Things got so bad that Parliament launched an official investigation into the sanity of top ranking naval officers and ship’s Captains (M’Quhae included) within the Royal Navy.

Parliament questioned how any self-respecting, let alone sane, officer of the Royal Navy could have allowed a report in which he claimed to have sighted a sea monster be willfully published in Great Britain’s most widely read newspaper.

As it turned out neither Captain M’Quhae, nor the Royal Navy had an answer, but rather than back down from their critics and detractors Captain M’Quhae along with other members of the crew of the HMS Daedalus took the offensive.

Captain M’Quhae worked in conjunction with an artist commissioned by the Illustrated London News, perhaps the London Times chief competitor, and produced a series of remarkable sketches and engravings of the HMS Daedalus sea serpent for all of the world to see.

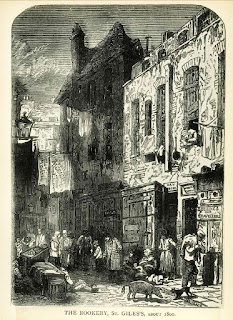

|

| Original Article and Sketches in Illustrated London News |

The British Admiralty was aghast, but the public ate up the pictures they saw in the Illustrated London News and the images were reproduced literally en masse around the world. It should also be remembered that in his attempt to explain away the sighting by the crew of the HMS Daedalus respected biologist Sir Richard Owen never once even bothered to consider the possibility that what the crew saw that day could have been some sort of species of “sea serpent” or some type of cryptid still unknown to science at the time.

At a time before published photography these professional images of the Daedalus sea serpent (many posted in this article) which were painstakingly based on the eyewitness accounts of the 6th of August 1848, firmly cemented the sighting of the HMS Daedalus sea serpent as one of the most remarkable, and at least to the Victorian reading public, one of the most believable encounters with a purported cryptid sea creature to ever take place in history.

Though even today there are those who attempt to discredit and explain away what the crew of the HMS Daedalus saw on the afternoon of August 6, 1848 including most recently a study published by the Skeptical Inquirer in 2015 which asserts that what the crew of the Daedalus witnessed that day was a rare species of whale swimming past their ship, there has never been a one-hundred percent satisfactory explanation to explain away the sighting of the HMS Daedalus as something other than an unknown monster of the sea.

All Officers kept a private journal. That was required by the Navy. They would have wrote what they saw and the Navy requires the journals be turned in.

ReplyDeleteTrue! Thank you for reading and taking the time to comment.

Delete