An Unavoidable Act of God? The Odd Tragedy of the Great London Beer Flood of 1814

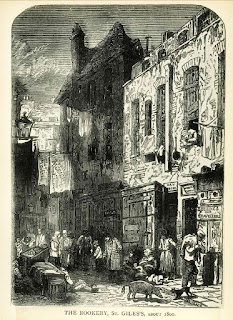

The Horseshoe Brewery, owned by the business conglomerate Meux & Company was located at the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street in London’s west end, a part of the parish of St. Giles, one of 19th century London’s most notorious slum neighborhoods.

Today, what was once the site of the Horseshoe Brewery is home to the fashionable Dominion Theatre, and is now surrounded by upscale hotels and restaurants. But back in 1814 the area, then known as St. Giles rookery, was a dense collection of closely packed tenement dwellings and slum cottages. It was one of nineteenth century London’s poorest neighborhoods, home to thousands of destitute Irish immigrants who lived underground in densely packed dank cellars, or in large families crammed into small one room apartments with little ventilation and few accessible outdoor exits.

On the afternoon of October 17, 1814 a seven hundred pound iron rung slipped from an enormous wooden vat containing approximately 150,000 gallons of porter, a dark thick beer, and the giant container burst!

The force of the onrushing tide of beer smashed through a brick wall separating the Horseshoe Brewery from the St. Giles Rookery and tens of thousands of gallons of beer flooded into the neighborhood.

|

| The Horseshoe Brewery circa 1814 |

One person, who had been going for a walk through St. Giles at the exact moment the wall of the Horseshoe Brewery collapsed during what became known as the Great London Beer Flood of 1814 reported in the weekly Knickerbocker newsmagazine that, “All at once, I found myself borne onward by a giant torrent which burst upon me so suddenly as to deprive me of breath.”

Hannah Banfield, a little girl of only four or five years old at the time, was sitting down having tea with her mother Mary in their single room cottage that adjoined the brewery on New Street in St. Giles, when the beer burst through the walls of their home and inundated their cottage. Both Hannah and her mother were swept away by the onrushing tide and drowned. Little Hannah Banfield and her mother Mary were the first victims of the Great London Beer Flood of 1814, but they wouldn’t be the last.

Only a block away from where the Banfield’s had sat down to tea, four mourners, all women and girls awaiting the return of their husbands and fathers from work that afternoon, were gathered around the tiny coffin of a two year old boy who had tragically died only the night before when a wave of beer fifteen feet high flooded the cellar in which they were holding their lonely vigil. A three year old named Sarah Bates was unable to escape the cellar in time and drowned beside the coffin of the dead little boy.

Recently arrived Irish immigrant Anne Saville, mother to the tragically deceased two year old John, was swept from the same cellar by the flood and also drowned.

The fifteen foot high wave of beer generated by the pressure and force of the ruptured vat continued to rush down New Street in St. Giles rookery and flooded the entire area. A few blocks away from where Sarah Bates drowned, the fifteen foot high wave of porter knocked over a brick wall of the Twisted Arms pub and trapped fifteen year old barmaid Eleanor Cooper beneath hundreds of pounds of rubble. Eleanor Cooper suffocated and died beneath the smashed bricks and broken masonry as the flood of beer rushed over her without anyone being able to hear her cries for help.

|

| Giant Wooden Beer Vats early 19th Century |

In total eight people died, all women and young children, on the afternoon of October 17, 1814 as a direct result of the Great London Beer Flood. Since the flood occurred in the middle of a Monday afternoon most able-bodied men who lived in St. Giles rookery, the majority of whom worked in low paying and largely unskilled manual labor jobs, were simply not home to even attempt to save the victims who were swept away and either drowned or crushed by the relentless flood of tens of thousands of gallons of beer.

The next day it was reported in the Times of London that, “Neighbors waded through feet of beer to find the bodies of those who lived next door.” The Times also stated that in the immediate aftermath of the Great Beer Flood, “Everyone remained completely quiet in order to try and hear the cries of those trapped in the wreckage.”

However, in addition to reporting on the carnage and suffering caused by the unexpected and even peculiar tragedy that befell the impoverished residents of St. Giles rookery, the London press of 1814 was also most unkind and stereotypes in print run rampant.

In the immediate aftermath of the Beer Flood London’s newspapers ran countless articles about supposedly indolent Irish immigrants drinking themselves into oblivion thanks to the free supply of beer that the disaster at the Horseshoe Brewery had so unexpectedly provided.

One newspaper report said that dozens of Irishmen died from alcohol poisoning and from drowning after having over-indulged in the pools of standing porter that remained left behind in the narrow streets of St. Giles rookery.

As it was, though there may have been some instances of drunkenness in the immediate aftermath of the Great London Beer Flood of 1814, there were no deaths as a result of intoxication or alcohol poisoning in the wake of the beer flood.

Truthfully, as the Times so succinctly stated on October 18, 1814 the real death and destruction consequent from the Great London Beer Flood was caused not by alcohol, but by the destruction of the Horseshoe Brewery itself. The lead article in the Times that day stated, “The bursting of the brew-house walls and the fall of heavy timber materially contributed to aggravate the mischief by forcing in the roofs and walls of the adjoining houses and dwellings.”

The stench of stale beer hung in the air in and around the St. Giles neighborhood for months after the tragedy.

|

| Satirical newspaper cartoon showing drunken Irish poor |

The only deaths that did occur were among the eight women and children who were so tragically swept away by the onrushing tide of thick dark beer that so unexpectedly and so quickly destroyed their impoverished homes on the afternoon of Monday, October 17, 1814.

Perhaps, the greatest tragedy of all is that the Great London Beer Flood of 1814 could, and maybe even should have, been prevented altogether.

At 4:30 p.m. on the afternoon of the flood, about an hour before the great disaster occurred, a man named George Crick who was a clerk that worked for the Meux Company in the Horseshoe Brewery, noticed that one of the iron bands that held together the giant wooden vats of beer was beginning to slip and come apart. He told his supervisor about the problem that he saw, but as it was not uncommon for these iron bands to slip slightly on occasion, no action was taken on the part of the management team of the Horseshoe Brewery to even check on the problem let alone to try and fix it.

Less than an hour later, the vat burst and a fifteen foot high wave of beer destroyed the two foot thick brick wall at the back of the Horseshoe Brewery and swept through St. Giles Rookery. Several employees from the Horseshoe Brewery were thrown skywards by the force of the bursting vat and ended up landing atop roofs on nearby houses. Four employees had to be rescued before they drowned in the flood of beer.

For their negligence, the owners of the Meux and Company conglomerate that owned the Horseshoe Brewery were taken to court for negligence, but the court ruled that the Great London Beer Flood of 1814 had been, “[A]n industrial accident and an unavoidable Act of God,” and that since it had been an act of God, or nature if you will, than no one could be held responsible at all for the disaster.

Not only was no one ever held responsible for the tragedy of the Great London Beer Flood of 1814 that killed eight innocent women and children in the impoverished neighborhood of St. Giles, but the Horseshoe Brewery and Meux & Co. whose negligence could be said to have caused the disaster in the first place, received a tax waiver from Parliament on the nearly 200,000 gallons of beer it lost as a result of the flood!

Slowly, over time in the aftermath of the Great London Beer Flood of 1814, iron rung wooden vats would begin to be replaced in breweries around the world by concrete lined, and later metal lined tanks and vats, which were far more secure and better at storing freshly brewed beer.

The Great London Beer of 1814 may officially have been ruled an unavoidable Act of God and industrial accident, but in reality, it was a senseless tragedy that was needlessly visited upon nineteenth century London’s most vulnerable population.

The Horseshoe Brewery went back into operation only days after the disaster and would continue to profitably operate in St. Giles rookery for the next one-hundred years until 1914.

Good Historical collection

ReplyDeleteThank you! Feel free to follow Creative History on social media! Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/creativehistorystories?mibextid=ZbWKwL. And on Instagram @creativehistorymikek

DeleteInteresting!

ReplyDelete