American Mutiny: The Story Behind the USS Somers Affair and How it Shocked America in 1842

Philip Spencer is a nineteen year old hard drinking party animal. He is a frat boy at sea and a perpetual ne’er do well who has a problem with authority. He left school as a teenager and ran away from home to find adventure on the high seas, but when his parents caught wind of where he was they quickly had him snatched up and brought back home against his will.

Philip’s father told him that if he wanted to go to sea to find adventure he would have to do so as a member of the United States Navy. Now, in the Autumn of 1842 Philip Spencer finds himself commissioned as an unwilling midshipman in the U.S. Navy aboard the newly launched brigantine the USS Somers.

His father, the man who gave Philip the commission in the United States Navy that he never wanted in the first place, is John Canfield Spencer, a former Congressman from New York and in November of 1842 the current Secretary of War (a position analogous to today’s Secretary of Defense) in the administration of John Tyler the tenth U.S. President.

It is November 26, 1842 and Philip Spencer, son of the United States Secretary of War is about to be accused, and later executed for being the ringleader behind the only shipboard mutiny in American Naval history.

|

| Philip Spencer |

Called the “Somers Affair” in the understated, stilted early Victorian Era parlance of the time, the mutiny that occurred aboard the USS Somers in November of 1842, and the subsequent way in which justice was so swiftly, and even brutally and arbitrarily meted out to its perpetrators, shook mid-nineteenth century American society to its core.

Launched in April of 1842 from the Brooklyn Navy Yard the USS Somers was the second United States naval ship to bear that name. The first ship named Somers had been a much smaller vessel that had been commissioned by the Navy during the War of 1812 and subsequently captured by the British during combat on the Great Lakes. Interestingly, the second USS Somers was about to meet an even more ignominious fate than that suffered by its namesake ship.

The second incarnation of the USS Somers was intended by the Navy to be a sort of experimental type of “training” ship, where young and aspiring naval officers like midshipman Philip Spencer would undergo an apprenticeship in seaborne command while on active duty naval exercises at sea. Of course, 1842 pre-dated the establishment of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, and it also came at a time before any form of regimented standardized training for new recruits had yet been put in place by the Navy.

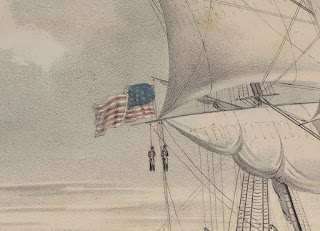

|

| USS Somers |

In the first half of the 19th century a lot of men aboard United States Naval vessels, from officers on down to common sailors, were often from the riff-raff of society, poor men with little future prospects in life, or with drinking problems, or criminals on the run from the law and looking to hide. In an era when adopting a new name could make a man an entirely new person, many looked to the Navy as a place to hide or run away. A great number were merchant sailors who had enlisted on a whim while being too drunk to even realize what they were actually signing up for in the first place!

It was thought at the time that a training ship like the USS Somers would be a great way to whip new prospective officers into shape and to instill in them the sense of discipline and responsibility that is so necessary for the successful operation of any warship while at sea.

A forty year old veteran commander, who had enlisted in the Navy at the tender age of 13 in 1815 to serve in the War of 1812, and who by 1842 had over a quarter century’s worth of naval experience named Alexander Slidell Mackenzie was named Captain of the Somers.

Despite a lifetime in the Navy, Captain Mackenzie was much more than just a sailor. He was an accomplished writer, having published numerous travel books in his lifetime up to that point, and he was an acquaintance of famed poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and a close personal friend of fellow New Yorker Washington Irving. Not only that, but Mackenzie’s connections were much more than just literary ones--his family was extremely well connected politically. His older brother John Slidell (Mackenzie had changed his name from Slidell to Mackenzie at the age of thirty-five to gain access to a rich uncle’s inheritance) was a state Senator from Louisiana while his other brother Thomas was Chief Justice of Louisiana’s State Supreme Court.

A learned and erudite man, who was well connected politically and who was certainly no stranger to the harsh life in the Navy with years of experience under his belt by 1842, it appeared that Alexander Slidell Mackenzie was an ideal choice to command the newly commissioned brigantine USS Somers on its first mission.

|

| Alexander Slidell Mackenzie |

After a quick trip from New York to Puerto Rico in the summer of 1842 simply to check the overall performance of the ship, the USS Somers left New York on September 13, 1842 bound for patrol off the west coast of Africa. On its maiden voyage the Somers was supposed to rendezvous with the frigate USS Vandalia in the port of Monrovia in Liberia, deliver dispatches intended for the Vandalia, and then conduct anti-slave trading operations off the African coast.

On November 10, 1842 the Somers docked in Liberia but learned that the frigate USS Vandalia had already set sail back across the Atlantic toward the United States. At this point, Captain Mackenzie turned his training ship around and headed for the Virgin Islands, hoping to be able to rendezvous with the Vandalia somewhere in the Caribbean before heading home to New York.

It was while the USS Somers was on its return trip to North American waters somewhere in the Caribbean that Midshipman Philip Spencer really began to put his mutinous plot in motion--supposedly.

Spencer had spent the past two months, white the Somers was deployed at sea, ingratiating himself with the rest of the crew. He had graciously given them all surreptitious and illegal gifts of rum and tobacco that he had used his personal connections to smuggle onboard the ship prior to the Somers departure from New York in September of 1842.

From the moment Spencer and Captain Mackenzie met in the summer of 1842 things had not gone well between the young midshipman and his commanding officer. Philip Spencer had previously been dismissed from a posting aboard a ship that patrolled off the coast of Brazil due to excessive drunkenness while on board and then assigned (thanks in large part to his father’s connections as Secretary of War) to the USS Somers.

Mackenzie had no patience, perhaps hypocritically so, for anyone who used his connections to gain advantage in the United States Navy. In his official report regarding the Somers mutiny Mackenzie wrote of Philip Spencer and his well known father, “I have no respect for the base son of an honored father…on the contrary I consider that he who by misconduct sullies the luster of an honorable name is more culpable than the unfriended individual whose disgrace falls only on himself.”

It’s obvious that Captain Alexander Slidell Mackenzie believed that a person, like himself, who was well connected had a reputation to uphold, but the also well connected Philip Spencer had other ideas.

Philip Spencer had never wanted to be the son of a well connected politician who was friends with the President of the United States--all that Philip Spencer had ever wanted to be was a pirate!

As the returning USS Somers sailed toward the Caribbean, Spencer began to tell the crewmembers he had befriended of his swashbuckling dreams. Apparently, he was able to recruit twenty other members of the crew to his piratical mission.

On the night of November 26, 1842 Philip Spencer approached the ship’s Purser, a man named James W. Wales. Spencer beckoned Wales to come with him and climb up some rigging where the two men could whisper in private out of earshot of any of the ship’s officers.

He told Purser Wales that, “I have recruited twenty men and we plan to seize the ship, kill any officers and enlisted men who are against us, and then cruise the Caribbean looking for plunder.”

Wales said that he sat there dumbfounded and didn’t utter a word until Spencer beckoned to another sailor named Elisha Small. According to Wales testimony Small and Spencer had a conversation in Spanish, a language which James W. Wales did not understand, but at the end of this conversation Elisha Small extended a hand towards Wales and said, “Glad that you could join us.”

James Wales said later that he reluctantly shook hands with Small, which apparently Spencer took as Wales’ tacit agreement to join the mutiny, and then the men all split up.

In the morning, Purser James W. Wales who happened to have a good relationship with all of the ship’s officers, and who had spent a sleepless night weighted down by a guilty conscience, decided to tell the Somers second in command, Lieutenant Guert Gansevoort, of what had transpired between him and Spencer the night before, and of the planned mutiny.

|

| Officers aboard the USS Somers |

Gansevoort promptly told Captain Mackenzie, and Mackenzie not wishing to act rashly, ordered that Gansevoort shadow Spencer’s every move that day and report back to him any suspicious activity.

Gansevoort reported back to Mackenzie that he had overheard Spencer having a conversation with the ship’s doctor about the Island of Pines, a notorious pirate hideaway in the Caribbean Sea off the coast of Cuba. He also reported that Spencer was seen studying the ship’s chronometer in an attempt to determine the Somers exact location at that moment in the Caribbean.

This was all the evidence that Mackenzie needed. He immediately had Spencer brought to him that evening and he rigorously questioned him regarding the mutinous conversation he had with Wales the night before. Under Mackenzie’s withering interrogation Philip Spencer admitted that he had talked about mutiny with Purser James Wales the night before but he insisted that he had only been joking.

Captain Mackenzie said, “This Sir, is joking on a forbidden subject..this joke may cost you your life!”

He then had Spencer put in chains and locked belowdecks.

And Captain Mackenzie was right. Even joking about committing a mutiny aboard a 19th century ship was no laughing matter. Speaking of a mutiny while onboard a ship at sea in 1842 is somewhat akin to threatening a terrorist attack on a public building today. Captain Mackenzie, as a commissioned officer in the United States Navy at the time, had every right to take the matter deathly seriously.

All of Philip Spencer’s personal possessions on ship were thoroughly searched and a document, written in Greek, was discovered. What became known as the “Greek Letter” was a detailed list of names marked willing, or unwilling, and it ended with the sentence, “The remainder of the doubtful will probably join when the thing is done…if not we will dispose of the rest.”

But there are several problems with the Greek Letter as supposed proof of a planned mutiny. For one thing, it lists several names of sailors that were not even onboard the USS Somers to begin with and it stated that Purser Wales, the man who had reluctantly agreed to the mutiny and brought the conspiracy to the officer’s attention in the first place was a “Sure thing”, though the document is not dated nor does it contain Philip Spencer’s name anywhere at all as the author.

Mackenzie and the other officers on board considered the “Greek Letter” to be a smoking gun; a damning piece of evidence that confirmed the presence of a conspiracy to mutiny aboard ship and since the document was found in Philip Spencer’s private possession he must, therefore, be the ringleader of the whole thing.

On November 30, 1842 an impromptu committee of ship’s officers reached a verdict that stated that Philip Spencer, Elisha Small and another sailor named Cromwell were, “Guilty of a full and determined intention to commit mutiny.”

Despite the fact that Spencer insisted that the three men had only, “Been playing at piracy,” and that the whole thing had simply been a made up story, the three men were sentenced to death.

Some accounts say that Mackenzie had badgered his ship’s officers to reach a hasty verdict and convict the accused out of his personal dislike for Philip Spencer. Other critics say that the whole thing was simply a practical joke gone out of control and that Mackenzie should have waited for the ship to dock in port in New York prior to pronouncing a sentence and that a proper military tribunal should have been conducted before any death sentence was passed.

Famed author James Fenimore Cooper, an acquaintance of Captain Alexander Mackenzie no less, was the leading advocate in the press for this position, and he along with many other leading journalists and writers of the time were shocked by the actions of Captain Mackenzie.

But all of the shock and outrage, as it were, was weeks in the future and would not arise until the USS Somers pulled into port at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City.

As it was Philip Spencer and his two co-conspirators were hanged until dead from the yardarms of the USS Somers and then promptly buried at sea--the only United States Navy personnel in American history to ever be executed for conspiracy to commit mutiny while aboard a ship at sea.

US Naval Academy Annapolis 1845

The events of the so-called Somers affair directly led to the establishment of the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland in October of 1845 in an attempt to better train officers to handle all potential contingencies while at sea, and instill a higher level of discipline and accountability among all sailors in the United States Navy.

Sounds like the spoiled child of a powerful politician got his comeuppance and then was lionized by a sycophantic press and other sundry libertines.

ReplyDeletePsychopath. Yeah, if someone jokes about wanting your job and has pirate fantasies you should definitely choke them to death and throw their corpse overboard like a slaughtered animal. There wasn't even a mutiny - there were *possible* plans for one. Doesn't quite seem a heavy enough matter to murder three people without even a trial first. You're being more savage than the public in 1840s America, ffs. Well, except all those libertines with their hippie objections to treating lives cheaply.

DeleteThe evidence does suggest that Spencer was doing more than joking, and the captain had to take the threat seriously. But Spencer's plan to become a pirate does seem hopelessly unrealistic, and it is hard to imagine a pampered playboy like that being able to adapt to the harsh realities of life as a renegade. So, it sounds like he did something stupidly reckless because his privileged upbringing had always protected him from consequences.

ReplyDeleteI suspect that if the mutiny had gone ahead then Spencer would have had little idea what to do next. It's likely that he would have swiftly lost the confidence of his supporters and been overthrown, and probably killed.

I also wonder if the captain feared that if he waited for a military tribunal on land to pass sentence then Spencer's family connections would ensure that he escaped any punishment.

Thank you so much for reading! Sorry for the late reply but all of your comments are well thought out and most probably true. I really appreciate the comment. It is probably true that the captain did believe Spencers family connections would have set him free.

DeleteThe captain had no idea how many others were in league with Spencer. He had to take action forestall a possible attempt to free Spencer and seize the ship.

ReplyDelete