Back from the Dead for Justice: The Story of the Greenbrier Ghost of 1897 and the Murder Conviction She Caused

Greenbrier County, West Virginia is located in the heart of Appalachia. It has a storied history dating back to the late 18th century. Famed orator and founding father Patrick Henry, as a young attorney, once defended a murder suspect in Greenbrier County years before an official courthouse was ever constructed there.

Eighty years later, a more modern and permanent courthouse in Greenbrier County would be the site of a Civil War hospital and witness the bloody carnage of battle as thousands of amputations, both confederate and union alike, would be performed on the courthouse grounds.

To this day many say that the Greenbrier County Courthouse, constructed in 1837 by a well known local brick mason named John W. Dunn, and relatively unchanged since it was originally constructed nearly 200 years ago, is haunted by the spirits of limbless young men dressed in blue and gray uniforms who wander its hallways at night looking for their eternal resting place.

As frightening as the prospect of Civil War ghosts may be, Greenbrier County, West Virginia, and its eponymous Courthouse are much more famous today for the spectre of one single murder victim who is said to have come back from the dead to bring the man who was responsible for her death to justice.

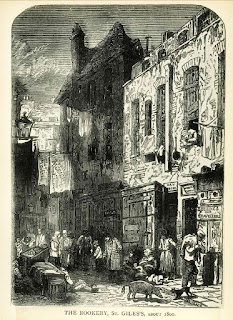

|

| Greenbrier County Courthouse circa 1900 |

Elva Zona Shue (nee Heaster) lived near the Greenbrier County Courthouse in Lewisburg, West Virginia. Elva, whom everyone in town referred to as Zona, had recently married local blacksmith Erasmus Shue after the pair eloped when Zona’s mother had disapproved of her beautiful young daughter’s relationship with a much older man.

The couple was married for three months, and all appeared happy and normal on the outside, but then on the morning of January 23, 1897 an eleven year old boy named Andy Jones, who was a neighbor of the Shue’s, and often helped around their house with chores, found Elva Zona Shue’s body lying pale, limp and lifeless at the bottom of the steps leading to the second floor of their log cabin home.

Jones, the young boy, rushed home and told his mother what had happened. Immediately, Andy Jones and his mother set off down the street to Erasmus Shue’s blacksmith shop where they informed Zona’s husband of the tragic discovery that had been made.

|

| Home of Elva Zona and Erasmus Shue |

Erasmus Shue, upon arriving at the scene, is said to have descended into a fit of anguish and he immediately called for local doctor and coroner George W. Knapp to come and attempt to resuscitate his wife.

As the three anxiously awaited the arrival of Dr. Knapp, Erasmus Shue clutched his young wife’s body to his chest and sobbed uncontrollably with grief.

When Dr. Knapp arrived he examined the body for several minutes and then announced that, “Mrs. Shue has died of an everlasting faint.”

In the parlance of the time the phrase “everlasting faint” was used to denote a heart attack.

At this point, things began to take a more bizarre and sinister turn.

Dr. Knapp asked the bereaved husband if he should attempt to resuscitate Mrs. Shue, or conduct a more definitive examination of the body to attempt to determine a more specific cause of death.

Erasmus Shue’s crying stopped and he told the doctor, “make no further examination of the body.” He then asked all who had gathered to leave at once after stating that he, “will personally take care of all burial arrangements,” for his deceased young wife. (from the Greenbrier Independent 1897)

Only mere hours after Zona’s dead body had been found, her husband, blacksmith Erasmus Shue, would place his young wife’s corpse into her coffin and personally help with her burial.

Those in attendance, who saw the young woman as she lay at rest in her casket, said that the side of her face was supported by a folded sheet and that her neck was covered by a giant scarf. When asked about why Zona was being buried with such a large scarf, Erasmus Shue would always tearfully reply, “It was her favorite.”

|

| Elva Zona Heaster and Erasmus Shue |

Despite the fact that no proper autopsy was ever performed on the body of Elva Zona Shue; that no one aside from Dr. Knapp, eleven year old Andy Jones and her husband Erasmus Shue even so much as looked at her dead body before it was prepared for burial and interred in the ground, and that her husband had controlled the entire burial process himself from beginning to end, no charges were brought against local blacksmith Erasmus Shue for the death of his young wife, and in fact, in the immediate aftermath of Elva Zona Heaster Shue’s untimely death no suspects were questioned and no investigation was conducted at all by local law enforcement in Lewisburg, West Virginia.

However, about a month later, Mrs. Mary Jane Heaster, the mother of Elva Zona Shue who lived just outside of town in a large old house atop Big Sewell Mountain began to tell her neighbors and the townspeople of Lewisburg, West Virginia, a most perplexing and unusual story.

The bereaved mother, Mary Jane Heaster started to tell neighbors that the spirit of her deceased daughter had visited her in the middle of the night on several occasions to, “tell on him,” and to, “set the record straight.”

Mary Jane Heaster claimed that her daughter’s spirit had visited her on four successive nights and told her that Erasmus Shue had been, “abusive and cruel,” and that he had savagely attacked her in a fit of rage and broke her neck.

Word of these ghostly visions spread across the tight-knit Appalachian community of Lewisburg like wildfire and soon, though claiming to be fearful herself of her recent brush with the supernatural, Mary Jane Heaster felt emboldened enough to approach Greenbrier County Prosecutor John Alfred Preston with the story she'd been told by the ghost of her daughter.

Mary Jane Heaster spent hours pleading her case to the Prosecutor based solely on her spectral evidence, and surprisingly, John Alfred Preston agreed to reopen the investigation into Elva Zona Shue’s death.

It is uncertain whether Prosecutor Preston actually believed all of Mary Jane Heaster’s ghost stories or if he simply gave in to local pressure after rumors about the possible murder of Zona Shue started to spread across Lewisburg. Perhaps, he believed that a thorough investigation into the circumstances of Zona Shue’s death had never been conducted in the first place and reopened the cause out of a sense of guilt and civic responsibility.

But it must be remembered that in 1897 it was not uncommon for loved ones to conduct seances and attempt to communicate with their departed relatives on a regular basis. The 1890’s were a time when spiritual movements such as Theosophism, a form of eastern mysticism based on communication with a spiritual realm founded by religious mystic and Russian immigrant Helena Blavatsky, were all the rage among many Americans. Given the spirit of the times it is also highly probable that Prosecutor Preston, along with a majority of the residents of Lewisburg, West Virginia, were persuaded enough by Mrs. Heaster’s spiritual testimony to reopen the investigation into her daughter’s death.

|

| Helena Blavatsky |

Once the case was reopened, Preston personally went to visit with Dr. Knapp and spoke with him about his examination of Elva Zona Shue’s body. Under questioning by Preston Knapp admitted that he felt, “he had not done a thorough enough examination of Mrs. Shue’s body.”

That was all the proof that John Alfred Preston needed.

He drew up an inquest and ordered that a proper autopsy be performed. Elva Zona Shue’s body was exhumed on February 22, 1897, a month after she had been interred in the ground, and examined in the local one room schoolhouse.

The autopsy lasted a full three hours. In the final autopsy report, despite the rapid decomposition of Elva Zona Shue’s flesh, it was stated that, “[T]he discovery was made that the neck was broken and the windpipe mashed...on the throat were the marks of fingers indicating that she had been choked.”

Erasmus Shue was immediately arrested and charged with the murder of his wife. He was held at the Greenbrier County Jail in Lewisburg to await trial.

At first, Erasmus Shue believed that he would be let out of jail and that the case against him would never come to trial at all due to lack of evidence, but while in custody Shue made the mistake of revealing the fact that he had been married twice before. It came to light that his second wife had also died under mysterious circumstances and it was reported that the cocky and confident Erasmus Shue boasted to his jail guards that he, “[D]reamed of marrying seven women and fathering dozens of children.”

The trial of Erasmus Shue for the murder of his wife Elva Zona Shue (nee Heaster) began in the Greenbrier County Courthouse on June 22, 1897. Erasmus Shue’s defense attorney planned to stick to just the facts and assured his client that there was not enough “real” substantial evidence to convict him of murder.

|

| Lewisburg, West Virginia in the 19th Century |

However, under cross examination Zona’s mother Mary Jane Heaster held steadfast to her assertion that the spirit of her deceased daughter had visited her on several occasions and recounted the ghastly circumstances of her death.

Mary Jane Heaster’s cross-examination under oath proved the most persuasive of all the testimony and the defense’s strategy of sticking to just the facts backfired.

As the Baltimore American for July 2, 1897 reported, “The principal evidence was that Shue’s mother-in-law, who testified that her daughter’s spirit had come to her at a seance and said Shue had killed her by breaking her neck...all the other evidence was circumstantial.”

Based on the strength of the story told by the ghost that had visited Mary Jane Heaster, and on the medical evidence brought forth as the result of an autopsy performed on a body that had been exhumed from the grave a month after it had been interred, Erasmus Shue was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison on July 11, 1897.

The night after his conviction an angry lynch mob formed outside the jail in Lewisburg and sought to hang the evil Erasmus Shue. To keep the mob away Sheriff’s deputies were forced to fire guns in the air and threaten to kill members of the angry mob if they came any closer.

Erasmus Shue never got the chance to marry seven times or father dozens of children. He died less than three years later in 1900 while an inmate at the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville after succumbing to a disease that he contracted while in prison. His body was burned and his ashes were interred in an unmarked grave on the prison grounds.

The ghost of Elva Zona Shue may or may not have come back from the dead, but she finally, in the end, got the justice she most assuredly deserved.

Today, just off of interstate Route 64 in West Virginia a state historical marker stands to commemorate, “the only known case in which testimony from a ghost helped to convict a murderer.”

Creepy!

ReplyDelete