Mars Fever: How an 1877 Error in Translation Led to a Fervent Belief in Intelligent Life on the Red Planet

“Scientists now declare that the many lines and spots on Mars represent...a most wonderful canal system which the inhabitants have constructed for the purposes of irrigation.”

-Quote from the Los Angeles Times 1907

It is 1877 and forty-two year old Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli is preparing to observe the planet Mars through a powerful new refractor telescope that has just been installed at the Brera Observatory in the city of Milan.

In a sense, Schiaparelli has been training for this moment for months. To effectively operate the refractor telescope and to accurately observe the Red Planet Schiaparelli needs steady hands and he has abstained for weeks from, “everything that could affect the nervous system, from narcotics to alcohol, but especially from the abuse of coffee,” he later writes, all in an effort to improve his observations.

Through the telescope Schiaparelli sees deep trenches, in the form of straight lines, criss-crossing the surface of Mars, which he names “canali” in his native Italian.

It appears that by naming the lines on the surface of Mars “canali” Schiaparelli intended to mean something more akin to what would be called a “channel” in English, which could imply a mass of water that might have naturally formed through either earthquakes or asteroid impacts, as opposed to the Italian word “canale” which is the direct translation of the English word canal. But when news reports of what Schiaparelli observed begin to make their way back to Great Britain and the United States, the Italian word “canali” is easily mistranslated into English as the word canal.

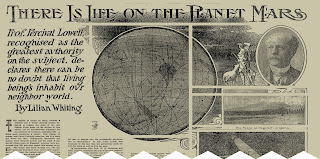

|

| Giovanni Schiaparelli and his map of "Canali" on Mars |

Only eight years prior in 1869, the Suez Canal which joins the Meditteranean to the Red Sea had been completed, and canals were considered the height of human engineering during the Victorian Era. When the public learned that “canals” might possibly criss-cross the Martian surface it was naturally assumed that these “canali” had to be the creation of a highly intelligent and advanced civilization. Mars Fever was born.

Oddly enough, the map that the meticulous Schiaparelli drew of his Mars observations, and its canals in 1877, has a striking resemblance to a map of the canals that run through Schiaparelli’s native city of Venice, so that despite his abstinence from caffeine, Giovanni Schiaparelli’s supposed objective astronomical observations of the surface of Mars may have been slightly prejudicial after all.

However, objective or not, created by intelligent life or simply natural formations occurring as a result of earthquakes or fissures in the Martian surface, or not, news of Schiaparelli’s discovery instantly went viral around the 19th century world.

In addition to canals, other astronomers across Europe and the United States began to observe that there were seasonal changes on Mars akin to the same types of changes that occur here on Earth. Nineteenth century astronomers believed that changes in the color of the Martian surface observed through their ever more powerful telescopes from light to dark indicated the existence of seasonally changing vegetation patterns on Mars.

In 1894, wealthy Bostonian businessman and astronomer Percival Lowell, used his own personal fortune to finance the construction of an astronomical observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, named the Lowell Observatory. Percival Lowell was one-hundred percent convinced that the “canali” that Giovanni Schiaparelli had seen and mapped on the Martian surface in 1877, were definitive proof of an intelligent, highly advanced Martian civilization, and set about using his own private observatory to prove it.

|

| Percival Lowell at his Observatory |

For fifteen years, from approximately 1894 to 1909, using powerful refractor telescopes at his observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, Percival Lowell intricately mapped and observed every inch of the surface of Mars. Lowell published three books detailing his Martian observations called Mars (1896), Mars and its Canals (1906) and Mars the Abode of Life (1908).

In these books Lowell minutely cataloged what he considered to be “non-natural”features that he believed he had seen on the surface of Mars. Among these “non-natural” features was an extensive canal system used for irrigation as well as drinking water, seas, and so-called “oases” where lush vegetation still grew in abundance on Mars. Lowell theorized that Mars was home to an advanced civilization that was “drying out” and slowly losing access to water due to environmental and atmospheric circumstances.

Lowell, in addition to being a well-connected New England based businessman and amateur astronomer was also a prolific writer, who beginning in the 1890’s began to contribute articles to widely read publications such as Atlantic Monthly and the New York Times. Despite some critics, even Schiaparelli himself, who steadfastly maintained that all of the “canali” he had observed on the surface of Mars could have been naturally occuring phenomena, Lowell’s contention that such canals and other “non-natural” formations on the Martian surface were incontrovertible proof of intelligent life on Mars, gained traction in both the scientific and journalistic communities.

In 1906 the New York Times ran a headline entitled “There is Life on the Planet Mars” above a feature article detailing the latest books published by Percival Lowell. This article and headline were picked up on and borrowed by newspapers across the United States. In 1911 the Times, once again referencing the work of Lowell, ran a front page headline that screamed: MARTIANS BUILD TWO IMMENSE CANALS IN TWO YEARS.

|

| Lowell by his Refractor Telescope |

True, many scientists and astronomers, particularly in the United Kingdom believed that the theories regarding life on Mars were complete nonsense, but many, especially those in the general public at large around the world fervently believed in the theories espoused and popularized by Percival Lovell.

And though today, all of Percival Lowell’s theories regarding evidence of intelligent life on Mars have been discredited by the scientific community, his fervent belief in an advanced Martian civilization had immense and long-lasting staying power.

As early as 1907 European astronomers such as Great Britain’s Alfred Russell Wallace began to question whether or not Mars was even warm enough to be habitable, and then in 1909, using a telescope much more powerful than the ones first used by either Schiaparelli or Lowell, French astronomer Eugene Antoniadi, published a work in which he argued that there was no clear observable evidence of any canal or channel like water formations on Mars at all.

But as late as 1916 when Percival Lowell passed away at the untimely age of sixty-one his hometown newspaper the Boston Globe reported in his obituary that, “while Dr. Lowell did not discover the planet Mars, he discovered almost everything worthwhile about the planet and his contributions to the astronomical field have been accepted the world over”.

In fact, even right up until the end of the 1920’s, Waeldemar Kaempffert, editor of both Scientific American and Popular Science Monthly, one of the most influential and popular science writers of the twentieth century and a personal acquaintance of Percival Lowell’s, was still defending the Martian intelligent life hypothesis in print.

It really was not until 1965 when NASA successfully sent the Mariner 4 unmanned spacecraft to the surface of Mars to take high resolution photographs of the planet, and it was revealed that the surface of Mars was completely dry and barren and dotted with tens of thousands of impact craters, that all serious speculation regarding the existence of intelligent life on Mars was finally put to rest once and for all within the scientific community.

|

| Image of Mars Surface from Mariner 4 in 1965 |

“Canals” as observed in 1877 by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli are, in fact, a natural and observable phenomena. Such “canali” are in reality, not bodies of water, but shifting formations of sand that are caused by cold gusts of wind along the sides of mountains and craters on the surface of Mars.

Though his theories regarding intelligent life on the surface of Mars have been completely discredited today, the memory of Percival Lowell continues to live on, and some of his astronomical ideas, such as the concept of building an observatory at the best possible location for actually looking skyward, are standard practice among astronomers today. And it was in 1930, at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, where the planet Pluto was first discovered by American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh.

Few people have ever done more to popularize astronomy as worthy of serious scientific study than Percival Lowell, and even though, what Giovanni Schiaparelli may have discovered on the surface of Mars in 1877 may not have had anything at all to do with Martian made canals, or canali, one thing is certain. Today, we still have a lot to learn about the mysteries of outer space and perhaps, Mars, our closest neighbor still has a lot left to teach us.

|

| Perseverance and Ingenuity on Mars |

On July 30, 2020 NASA launched its newest Perseverance Rover equipped with the small robotically operated helicopter Ingenuity designed to explore and map the surface of Mars in greater detail than has ever been done before. Perseverance is the first step in NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, which one day, hopes to culminate with a manned mission to Mars. As Perseverance continues to stream detailed color images and video of Mars back to earth, many of the theories first advanced so long ago by Percival Lowell are beginning to resurface yet again and be looked at in a new, more plausible, light. Perhaps the twenty-first century will one day be remembered as a time when “Mars Fever” once again returned to earth.

Comments

Post a Comment