The Brooks/Sumner Caning on the Senate Floor and the Harlot Slavery: May 22, 1856

On Thursday, May 22, 1856 thirty-seven year old Congressman and former United States Army Captain decorated veteran of the Mexican-American War from South Carolina, Preston Brooks walked into a nearly deserted Senate chamber.

With Brooks, that day as he walked onto the Senate floor, was his fellow Congressman from South Carolina, attorney, Laurence M. Keitt. Brooks and Keitt had waited up above, in the gallery, nearly the entire day for the Senate floor to empty. It is their desire that no ladies be present to witness what they are about to do.

The Congressmen from South Carolina are there to confront Senator Charles Sumner, Republican from Massachusetts, leader of the abolitionist faction in Congress and one of the most eloquent orators in the United States over remarks he made in a speech two days prior.

|

| Preston Brooks |

When Brooks and Keitt first entered the Senate chamber that day it was Brooks’ intention to challenge Sumner to a duel for having slandered his cousin, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler, in a two day long riveting anti-slavery speech he had made on the Senate floor which he had entitled “The Crime Against Kansas”.

In that marathon speech, which dealt with whether Kansas would be admitted to the Union as either a slave or a free state based upon the popular vote of the white male residents of the territory, Sumner had referred to the southern Democratic faction which sought to admit Kansas to the Union as a slave state as, “murderous robbers from Missouri.”

Sumner asserted that those southern pro-slavery elements which had traveled to Kansas over the past two years, between 1854-56, to try and sway the vote regarding slavery and the popular sovereignty issue through the use of force and intimidation were, “Hirelings picked from the drunken spew and vomit of an uneasy civilization that have committed the rape of a virgin territory compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery.”

Sumner singled out Senator Andrew Butler from South Carolina for his especial wrath and said of him that, “[T]he Senator from South Carolina (Butler) believes himself a chivalrous knight of honor and courage...he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him--I mean the harlot Slavery.”

The mocking of Senator Butler didn’t end simply with Sumner labeling the South Carolinian’s commitment to slavery as a love affair with a whore, it got even more personal.

“He touches nothing,” Sumner said of Butler in the same speech, “which he does not disfigure with error, sometimes of principle, sometimes of fact. He cannot open his mouth, but out there flies a blunder.”

|

| Charles Sumner |

Congressman Preston Brooks, watching the speech from up above in the gallery that day, was enraged. Brooks, who was a first cousin of Andrew Butler and who considered himself the noble embodiment of a perfect southern gentleman became incensed at the sexual innuendo and personal attacks that Sumner used against his cousin on the Senate floor.

Young, hot-headed and with his blood up, Brooks strode onto the Senate floor two days later with the elder Congressman Keitt by his side and sought to confront the smooth and eloquent Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

Originally, it was Brooks plan to do the gentlemanly thing, and as a man of honor himself, challenge the Senator from Massachusetts to a duel by pistols at ten paces as was the custom in his home state of South Carolina. Either the abolitionist Sumner would prove himself to also be a gentleman of honor and accept the challenge, or he would back out of the duel, and thereby show the entire nation that he was (as Brooks suspected) a spineless coward.

However, as Brooks and Keitt walked toward Senator Sumner’s desk, Keitt whispered in Brooks' ear, “Dueling is for gentlemen. Sumner is no better than a drunkard and not worthy of a duel.”

Brooks reached Sumner as he sat writing at his desk. He stood behind the Senator and calmly announced, “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and on Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

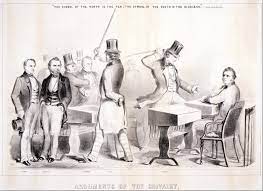

|

| Brooks and Keitt approach Sumner |

As Sumner turned to stand up Brooks swung his heavy metal tipped wooden cane and brought it down hard upon the Senator’s head. Before Sumner could even stand up blood was already pouring down his forehead and over his eyes from the repeated blows of Brooks’ cane.

Sumner was knocked to the floor of the Senate chamber, nearly unconscious and trapped beneath his own desk which was bolted to the floor. Brooks’ like a man possessed by rage continued to strike Sumner again and again with his cane. Only after wrenching the desk free of the floor and finally struggling to his feet was Sumner able to stagger away from Brooks in fear of his life.

Blinded and bloodied with his arms outstretched, Sumner half walked and half crawled his way to the aisle, but Brooks pursued the battered older Senator. He caught up to Sumner again and continued to beat him until his cane snapped in half.

“Oh Lord! Oh! Oh!” Sumner gasped on his hands and knees before Brooks bludgeoned him in the face with the gold head of his broken cane and he passed out unconscious in a bloody heap on the floor.

An unremorseful and satiated Brooks later said of Sumner and his beating that, “he bellowed like a calf,” before he succumbed.

Not satisfied, Brooks lifted up the unconscious Sumner by his lapels with one hand, and continued to beat him across the face with the remnants of his cane held in the other.

Fearing that Senator Sumner may be killed in the attack, some of the few remaining Senators and Congressman who yet remained in the chamber that day tried to intervene, but Keitt raised a revolver in the air and shouted, “Let them be! Let them alone!”

Eventually, other Congressmen and Senators were able to shove aside Keitt and finally, after the attack had gone on for several minutes, Representatives Ambrose Murray and Edwin Morgan of New York were able to restrain Brooks.

After being held by Murray and Morgan and dragged away from the bloody and beaten Sumner, Brooks quietly turned without saying a word, and walked slowly off the Senate floor and out the door of the Capitol.

|

| Congressman intervene in the Brooks/Sumner attack |

Charles Sumner was carried to a cloak room, sort of like a large closet, in the Capitol building where he slowly regained consciousness. He received medical attention and several stitches to the wounds on his head while still in the cloak room before being escorted by carriage back to his lodgings where he received further medical attention.

In the aftermath of the attack Preston Brooks became a hero in the south while Charles Sumner gained instant notoriety as a martyr to the abolitionist movement in the north.

The south’s largest daily newspaper The Richmond Enquirer of Richmond, Virginia, praised Preston Brooks’ attack as, “good in conception, better in execution and best of all in consequences.”

Many in the south publicly mocked Sumner and claimed that the cane which Brooks used had not been heavy enough to cause any serious injury and that he had only been struck a few times. Southern newspapers and sympathizers tended to liken the beating of Senator Charles Sumner to the spanking of a child and accused the Senator from Massachusetss of being a crybaby.

In reality, as a direct result of the assault, Senator Charles Sumner suffered chronic and debilitating pain for the rest of his life and symptoms of what would now be called traumatic brain injury. He would spend three years recovering from his injuries before he was finally well enough to return again to his seat in the United States Senate on the eve of the Civil War.

For his part, Preston Brooks always steadfastly maintained that he never intended to kill Senator Sumner and that had he wished to kill him he would have used a different weapon.

Brooks also stated that he, “meant no disrespect to the United States Senate through his actions”.

He was arrested shortly after the caning and tried in Washington D.C. where he was found guilty of misdemeanor assault and fined $300 (about $8,500 in today’s money) though he neither faced, nor received, any time in jail.

Brooks resigned from his Congressional seat on July 15, 1856, but a little over two weeks later he was reinstated by his constituents through a special election and he won another term in office the following year, though karma would eventually catch up with Preston Brooks and he would die of croup, a severe respiratory infection in 1857, at the young age of 38.

|

| Type of cane used by Brooks in the attack |

Due to the spectacle of Sumner’s caning on the Senate floor, voters in the north would rally to the abolitionist cause and elect Republicans to congress in overwhelming numbers during both the 1856 and 1858 election cycles. Abolitionism as a movement, and the nascent Republican Party as a whole would continue to grow rapidly, culminating in the election of Abraham Lincoln as the sixteenth President of the United States in 1860.

If nothing else, the caning of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina on May 22, 1856 was one of the first events that showed how polarized the United States had actually become over the issue of slavery in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

And perhaps, unwittingly, Preston Brooks through his use of violence on the Senate floor helped precipitate the end of the most violent and dehumanizing practice in American history--the harlot Slavery.

Comments

Post a Comment