The Homicidal Pastime: How Teddy Roosevelt & Harvard University Saved American Football in 1905

It is October 30, 1897 and up to that point the much more talented University of Virginia team has been dominating its rivals from the University of Georgia on their own home turf in Atlanta.

The Georgia faithful are becoming disappointed and fast losing hope. Prior to kickoff the University of Georgia student newspaper The Red and Black had called this game, “the greatest athletic event that has ever occurred in the south.”

In that same article the student newspaper also went on to say, “Every man on both teams realizes the fact that there is much at stake and each one will enter the game with a determination to win or die.”

To Win or Die...little did the undergraduate journalist who penned that article realize how prescient those words would become on that Saturday afternoon in October of 1897.

Hill takes the ball and runs straight at the University of Georgia defensive line. Georgia Lineman Richard Vonalbade Gammon rushes forward to tackle the ball carrier Hill. He leaps in the air and misses Hill entirely. Gammon flips end over end and crashes down hard on the ground landing head first.

As Gammon lays inert on the field players from both teams run over his back and trip and fall on top of his unconscious body. When the play ends only seconds later everyone else, except for Richard Vonalbade Gammon, instantly pops back up off the ground.

Concerned spectators, several doctors among them, rush onto the field and crowd around the eighteen year old Gammon as he continues to lapse in and out of consciousness. For nearly an hour University of Georgia Freshman Richard Vonalbade Gammon lays untreated on the football field with a fractured skull.

Finally, he is carried off the field on a blanket and brought to a nearby Atlanta hospital where he dies eleven hours later with his grieving parents by his bedside.

Richard Vonalbade Gammon is only one of the estimated 300 players killed while playing football for prep schools and universities all across America during the decade between 1895 and 1905.

American football at the turn of the 20th century was a much different game than the one we sit down to watch every Thanksgiving Day after stuffing ourselves with as much turkey and pumpkin pie as we can eat.

|

| Human Wall Formation ca. 1900 |

Every year, usually on Thanksgiving weekend, Harvard and Yale would play a game that often drew up to 30,000 fans and was a sort of Super Bowl of its day, being hyped up and covered by newspapers all across the United States. But it wasn’t just the lack of a professional league that made the game of football so different 120 years ago, it was the way in which the game was played back then that would shock most football fans today.

At the start of the 20th century American football was a lot like the sport of rugby, only more brutal and violent and with fewer rules. The football itself more closely resembled the size and shape of a rugby ball today and would have even been more akin to a misshapen medicine ball, or a small watermelon, than to a modern American football.

|

| Harvard Yale Game 1905 |

Teams had three plays to advance the ball a total of five yards in order to achieve a first down and there was no such thing as a forward pass. The only way to move the ball down the field was to try to methodically run it through the other team’s defense, or toss the ball backwards, and hope that an opening would form to enable you to then run past the opposing defenders.

There was no “fair catch” rule in place to protect defenseless players given the unfortunate task of returning punts and a player carrying the ball was not considered down by contact until he literally completely stopped trying to move at all.

Punching, biting, kicking, hitting in the back and even choking were all common and accepted forms of “tackling” prior to 1906. No form of physical contact was technically deemed unnecessary, too rough or illegal and there was almost no such thing as a penalty.

Additionally, players wore little to no protective equipment, and as a result of the physical nature of the game, players tended to bunch up towards the middle of the field in brutal and violent human wall type formations in order to try and advance the football the requisite two yards at a time that were required to achieve a first down in three plays.

Broken necks, fractured skulls, snapped spinal cords and internal hemorrhaging were as common on the gridiron back then as pulled hamstrings, turf toe and (unfortunately) concussions are today. Year after year the number of deaths on the collegiate football field mounted.

After the death in 1897 of University of Georgia Freshman Richard Vonalbade Gammon, Harvard University President William Eliot said, “the game grows worse and worse in regards to foul and violent play...there is the ever present liability of death.”

That same year (1897) after attending the Harvard/Yale Thanksgiving Day game, heavyweight boxing champion John L. Sullivan when asked what he thought of gridiron football said, “There’s murder in that game.”

Yet despite the violence and despite its many critics, college football became and remained, wildly popular. Schools took great pride in their team’s accomplishments and just as there may have been murder in that game there was also a lot of money to be made in that game through gambling and ticket sales.

In spite of the temporary cancellations of football programs in schools throughout the United States due to player deaths during the 1890’s and 1900’s the game always came back by popular demand. Played only once per week during the fall and early winter months when nothing much else in the sporting world was going on, football naturally lent itself to pregame hype and speculation that made betting on the games enormously popular and profitable. Similarly, the violence of the game itself attracted young men to the football field who looked on the sport as a sort of combat where they could prove their courage and manliness.

President Theodore Roosevelt was one such believer in the edifying martial and masculine qualities of American football. Roosevelt, known to history for his own personal courage and manliness as the rough rider who led the brave charge up San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War in 1898, believed that football was good for young American men as a means to develop physical strength and mental toughness.

However, the 1905 season would convince even President Theodore Roosevelt that the violence and brutality in American football had gone too far and that the game needed to be changed.

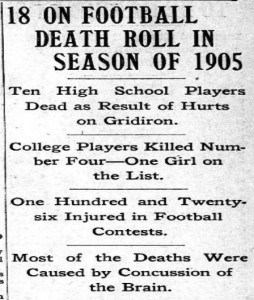

During September and October of 1905 nineteen players, all of them between the ages of 17 and 22, died while playing football at America’s colleges and universities. The most common cause of death was deemed to be head injuries sustained after the play was over and the player was lying helpless on the ground.

On October 15, 1905 The Washington Post reported: “Nearly every death may be traced to unnecessary roughness. Picked up unconscious from beneath a mass of either team’s players, it is generally found that the victim has been kicked in the head or the stomach, causing internal injuries or fractured skulls.”

Newspapers across the nation started to publish weekly tallies, accompanied by photos, of the names of players who had been killed in the previous weekend’s football games. The national press dubbed it “Football’s Death Harvest” and began referring to the sport as “Slugball”. Cartoons depicting football players being stalked by the grim reaper appeared in editorial columns from coast to coast.

The public outcry against the violence and brutality of collegiate football in 1905 was enormous and unstoppable.

Finally, President Roosevelt wrote to coaches and athletic directors at the Ivy League schools of Harvard, Yale and Princeton and requested a conference at the White House to discuss rule changes aimed at improving the safety of the game.

Roosevelt wrote to the universities, “I want to talk over certain football matters with you. I earnestly hope that you will be able to come.”

During the conference President Roosevelt urged the representatives from the Ivy League schools to implement rule changes that would make the game less deadly. He called on them to meet with other collegiate representatives from schools across the nation to discuss and implement modifications to the rules that would reduce the number of on the field fatalities and allow the game to continue being played at institutions of higher learning.

At first, the Ivy League coaches and athletic representatives were hesitant to draw up any concrete rule changes to the game out of fear that doing so would somehow make football less popular. But then, a tragedy in November of 1905 would abruptly change everyone’s mind and precipitate immediate changes to the rules of the sport.

During the first half of a game between New York University and Union College on November 25, 1905 Union College Fullback William Moore was tacked from behind and buried beneath a swarming horde of players. When the play was over, nineteen year old William Moore’s head was buried, facedown in the mud with his body unconscious and unable to breathe because his face had been pushed so deep underground.

An autopsy that evening at Fordham Hospital showed that Moore had died from a combination of bleeding on the brain and asphyxiation.

The next day, Sunday November 26, 1905, The New York Times ran a big bold headline on the frontpage: THE HOMICIDAL PASTIME that was accompanied by an emotionally charged article which called for an end to all football programs across the United States.

Since this was the first fatality that had occured during a football game that had been played in New York City and because it was the first time that a death during a football game had become frontpage news in America’s largest media market, the outcry calling for an end to American football now became not just national, but international as well.

People in Australia and the United Kingdom proposed that Americans adopt either rugby or Australian Rules football as their national collegiate sport in lieu of the inherently violent nature of American football.

After years of death and negative publicity many college Presidents began to take them up on their suggestion and some cancelled their school’s football programs entirely replacing them instead with Australian Rules football or rugby programs.

Realizing that they had to act, and after the urging of President Roosevelt yet again, representatives from the major Ivy League schools finally met on January 6, 1906 to propose rule changes to improve the safety of American football.

Harvard University, and their safety minded President William Eliot, took the lead in proposing innovative new rule changes to the sport.

The Harvard delegation recommended that players be spaced out on the field to prevent mass plays where players needlessly piled on top of one another after a runner was already down. They also recommended that teams be required to move the ball ten yards over the course of four plays to achieve a first down instead of five yards over the course of three plays. They proposed that once any part of a player’s body (other than his hands or feet) touched the ground after contact that he be ruled down and the play itself be ruled over. The Harvard team also wished to implement a “neutral zone” between the offense and defense that could not be crossed by players on either side until after the ball was snapped.

And, perhaps, most creatively of all, Harvard proposed that use of the forward pass be adopted as a legal means of moving the ball down the field. To facilitate the forward pass the Harvard delegation also wished to create a new position called Wide Receiver, or Split End, as it was called at the time.

Between January and April of 1906 Ivy League representatives met at least half a dozen times to discuss possible rule changes to the football but they remained deadlocked as winter turned into spring.

Finally, out of pure desperation, Harvard threatened to eliminate its football program entirely if the changes that had been proposed weren’t immediately adopted. Fearing the loss of the most popular team in the country, as well as their most bitter rival, Yale and Princeton along with Penn State, NYU and Columbia University all relented and adopted the Harvard proposal.

The historic 1906 football season would see the first use of the forward pass; the first time that a neutral zone would be employed at the line of scrimmage; the first time that a runner was ruled down by contact and the first time that a penalty would be called for unnecessary roughness and unsportsmanlike conduct.

Though intermittent deaths would continue on the collegiate football field for years to come, and helmets would not be widely adopted by players until the 1920’s when the NFL was formed, all of the rule changes that were adopted in 1906 still remain in effect to this very day at both the professional and collegiate levels of American football.

Those rule changes have saved hundreds, if not thousands, of young lives over the past one hundred plus years and they remain a testament to a time when Harvard University and President Theodore Roosevelt may have saved the great American game of football from extinction.

Comments

Post a Comment