His Majesty's Death: The HMS Jersey-- British Prison Ship in New York Harbor

“They were merely walking skeletons without clothes to cover their nakedness...covered with lice and vermin from head to foot.”

--Captain Alexander Coffin prisoner aboard HMS Jersey 1781

As day breaks you can see it rising like a flat-topped hill in the distance. The gutted hulk sitting there motionless and sunk in the mudflats of Wallabout Bay that you’ve heard about in rumors, the most infamous of rumors, among men in the army. Your heart rate quickens as your footsteps take you closer.

While you’re still over two hundred yards away from it, already, you can smell it. The stench of the combined filth and decay of over 1,000 starving and dying men being lifted to your nostrils as it’s borne aloft by the early morning breeze.

Your knees tremble. You feel faint and think of running away. But one glance to the right and left and you see the Redcoats standing guard over you and you realize that any attempt at escape will end either with a British bayonet thrust between your shoulder blades or a musket ball through the back of your head.

Within minutes you’re being rowed out into the shallow water in a small dinghy. Soon you’re right before the featureless, rotting, black wooden hulk of the British prison ship HMS Jersey.

The first thing that you hear as you set foot on deck are the shouts of British soldiers yelling, “Rebels! Turn out your dead! Rebels! Turn out your dead!” Skeletal, naked bodies scurry up on deck. Their skin is covered with sores; lice crawl all over them in such numbers that they no longer seem to notice. The men carry large wooden tubs across the bare deck. They walk to the very edge of the deck and then unceremoniously dump corpses from their tubs overboard. The corpses will lay rotting in the mud until the tide comes out to take them away.

For a moment, you stand motionless, numbed by the horrors that you are witnessing. You see more skeletons lurch on deck. These men are also carrying tubs, Their wooden tubs are filled with human waste from below that they too dump overboard, creating the swampy morass that the British prison ship Jersey sits atop. This site is the future location of what will one day, in the distant future, become the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

For the second time that morning you feel as if you might swoon. Before you’re prodded down below by a British bayonet, you notice one of those skeletal forms walk close by you. He is completely naked. He says to you, “Better take your clothes off lad. Better to be naked down below. There’s no air and your clothes will only get eaten to rags by the vermin.”

It’s far worse down below…

The British prison ship HMS Jersey is one of sixteen prison ships used by the British navy during the American Revolution. Each British prison ship is like something akin to a floating death camp but the HMS Jersey is the biggest and the worst of them all. Those who have been there give it a very simple nickname--Hell.

It is located in the East River just off the coast of Brooklyn and between the modern day sites of the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges. At any one time there are upwards of 1200 American prisoners of war packed into a gutted old vessel that was originally built to accommodate no more than 400 men.

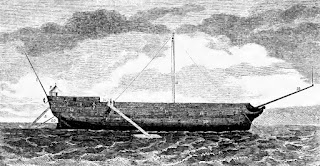

Originally commissioned in 1736 as a 60 gun British Man-of-War the HMS Jersey sees service in The War of Austrian Succession and in the Seven Years War of 1754-63 as well. In the early 1770’s the British temporarily converted the Jersey into a hospital ship before sometime in 1779 removing all spars and masts and gutting the ship entirely to convert the Jersey into the largest prison ship of the American War for Independence.

For three quarters of the day, and all night in pitch darkness, the men aboard the Jersey are kept locked below-decks. All portholes on the ship have been sealed shut and in their place the British have drilled small barred holes spaced every ten feet apart for air. There isn’t enough oxygen below-decks to even light a candle. It truly is worse down below. In the summer the men lie naked in the darkness, writhing over one another while being covered by insects and bitten by rats in the stifling heat. In the winter the men will literally freeze to death where they lay due to frostbite and exposure.

At least a dozen men die each day aboard the HMS Jersey. Their bodies are tossed overboard each morning by the other prisoners still healthy enough to carry them.

“Covered in filth...pallid with disease...emaciated with hunger and anxiety,” one survivor recalled.

In total 8,000 men will pass through the hell-hole of HMS Jersey between 1779 and 1783. Only 1,400 will live to tell about it. The list of what can kill you aboard the Jersey is endless: exposure, starvation, smallpox, yellow fever, dysentery, cholera, beatings even suicide by madness.

If exposure doesn’t get you then hunger probably will. Food rarely comes at all and when it does it is all but inedible. “The bread was mouldy and full of worms. It required countless rapping against the deck before the bugs fell out,” recalled survivor Ebenezer Fox years later.

Along with starvation and exposure the ever present specter of disease hovered everywhere. The Jersey wasn’t so much a prison ship floating in open water as it was more a shallow tub moored in and filled with filth. In the words of Continental Army soldier and prisoner of war Ebenezer Fox, “The Jersey was embedded in the mud. All the filth from upwards of 1000 men was daily thrown overboard and would remain there. We would boil whatever little food we had in this tepid filth…”

Approximately 4,500 American soldiers will die as a result of combat during our nation’s War for Independence. Nearly 20,000 American soldiers and sailors will die during the war as a result of disease or starvation. Perhaps as many as one third of those deaths will occur as a result of maltreatment and horrid conditions aboard the HMS Jersey.

In the Summer and Fall of 1776 British forces drove George Washington’s heavily out-numbered Continental Army out of New York City. For the next four years British and American forces will fight running battles between New York and the American capital of Philadelphia leaving New Jersey a war ravaged landscape. Manhattan will become the epicenter of the British war effort to subdue their rebellious North American colonies. At peak strength there will eventually be 40,000 British and Hessian (German mercenaries hired by the King of Great Britain) soldiers in and around present day New York City.

In October of 1781 British General Lord Cornwallis surrendered his army to American and French forces led by George Washington at the battle of Yorktown in Virginia, effectively ending combat operations in the United States, but the British will not withdraw their forces from New York until 1783.

During the course of the fighting across the states of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania the British capture thousands of American soldiers and arrest hundreds more American patriots on suspicion of sabotage and subversive behavior.

Originally, the plan had been to send these captured soldiers and subversives back to Europe where they could be imprisoned for the duration of the rebellion. But as thousands of American prisoners of war were captured during the battle for New York in 1776, and Washington’s Continental Army simultaneously proved more resilient than the British had bargained for, this plan quickly became too costly and logistically impossible to execute.

Realizing the impossibility of exiling large numbers of American prisoners of war to Europe, and lacking both the will and the capacity to erect large prison camps on the American mainland, the British turned to the use of prison ships docked in the harbors of major American cities, foremost among these being the HMS Jersey.

Typically, during 18th century warfare, prisoners would be exchanged between sides or sometimes ransomed to freedom. But because the British considered American’s to be a form of traitors, rebels or enemy combatants not worthy of the status of soldiers and because the Continental Army rarely had any money to pay the men it actually had under arms at the time, let alone pay ransoms for those that had already been captured, thousands of souls were left to languish and die aboard floating hell's like the HMS Jersey for the duration of the war.

Prison ships were designed by the British to be instruments of psychological terror for both patriots and civilians alike--and they worked. Sitting still in the harbor, decaying hulks of wood rotting away and reeking of pestilence, British prison ships were a constant reminder to the American population of the extremes to which the British Empire would go to crush rebellion in North America.

In it’s time the prison ship Jersey generated wild rumors among patriots and loyalists alike. The HMS Jersey was a reminder to all of those who lived through it of how brutal eighteenth century warfare could be despite the fact that history has, for the most part, portrayed the American Revolution as a conflict fought between two opposing gentlemanly nations.

For the most part, as time went on, the HMS Jersey was largely forgotten by the collective American historical memory except for the occasional sun bleached bone that would wash ashore on the banks of the East River from time to time. However, in 1902, while laying down the foundation for a new dock, workers at the Brooklyn Navy Yard discovered the exact spot where the prison ship HMS Jersey had been. With this discovery, the horrors and sufferings of all those who had been aboard the HMS Jersey resurfaced in American consciousness. In 1908 President William Howard Taft dedicated the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park Brooklyn.

Today that monument still stands in honor of the over 11,000 American patriots who gave their lives for our country aboard the HMS Jersey and all the British prison ships during our nation’s War for Independence.

Comments

Post a Comment